Delivering a Knockout

By Kerry Ludlam, Photography by Richard Corman and Jack Kearse

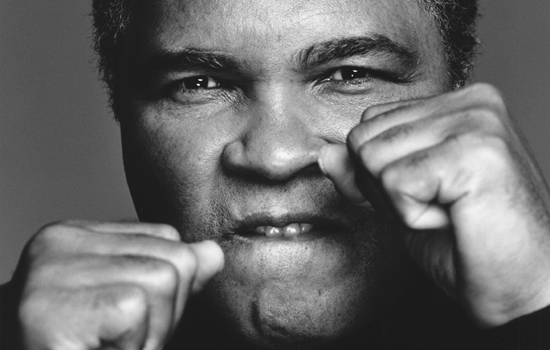

Richard Corman/Wave Reps

Muhammad Ali has faced some of boxing’s toughest competitors—Sonny Liston, Joe Frazier, George Foreman. But who knew that he would face his toughest opponent more than a decade after his Rumble in the Jungle with Foreman? In 1984, Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (PD), a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects an estimated 1 million Americans.

Ali is one of 10,000 patients treated each year at Emory for PD, which may cause slurred speech, tremors, and slowed movements. He is a long-time patient of Mahlon Delong, William Timmie Professor of Neurology, who in the words of Lonnie Ali, wife of the celebrated fighter, “has been the best medical intervention in Muhammad’s life.”

PD is a complicated illness to treat. The interventions needed for comprehensive care are wide-ranging, and the number of specialists involved often necessitates a daunting schedule of appointments for patients and caregivers to navigate. DeLong, whose studies have led to the development of effective surgical approaches for the treatment of PD, is one of the many Emory providers who provide this complex care.

In addition to a movement disorders neurologist, patients with PD often need the help of a psychiatrist, neuropsychologist, physical therapist, geriatrician, sleep specialist, speech therapist, social services worker, and occupational therapist, among others. But making the rounds of all those professionals takes much longer than a boxing match.

“Arranging all the specialists a person with PD really should see could take six months to a year to schedule appointments and get a plan in place,” says Stewart Factor, Vance Lanier Chair of Neurology. “Meanwhile, who knows how much the disease has progressed?”

Recognizing the need to get all of a patient’s care efficiently in one place at one time, Factor and his colleagues in Emory’s Movement Disorders Program set out to create a new strategy—one that is comprehensive and integrated.

Round 1: Making an impact

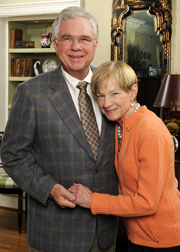

As the Emory team began making plans for a comprehensive approach to PD, Atlanta resident Merrie Boone was dealing with her own diagnosis of the disease. She and her husband, Dan, had visited centers all over the country to find the right treatment fit for her, but a consultation with a California specialist led them somewhere unexpected—back home. “We had flown to California to find out that the best care was in our own backyard,” says Dan Boone.

Not only did Merrie Boone become a patient at Emory, but the Dan and Merrie Boone Foundation also is helping Emory realize its vision for PD care. The Boones have pledged more than $600,000 to accelerate Emory’s development of a comprehensive center, and their gifts have allowed Factor to enroll up to four patients a month in the comprehensive care program. The program allows patients to see all the specialists that they need over the course of two days. A nurse coordinator manages the full spectrum of PD services to ease the burden on patients and families.

That condensed schedule is intense, but the result is a win-win. In most cases, the approach has increased patient satisfaction and fostered compliance to treatment regimens, and it has allowed doctors and other providers to work as a team to provide comprehensive care.

For the Boones, the goal is simple. “We wanted to do something that improved the patient experience and their overall quality of life,” Dan Boone says. “We wanted to make an immediate but lasting impact.”

For Jimmy Long, they did.

Round 2: Personalizing treatment

After developing a telltale tremor in his left hand, Long was diagnosed with PD in his hometown of Augusta, Ga. At that time, he had one overriding fear. “My whole life I’d told myself I didn’t ever want to be in a wheelchair,” he says. “And I wasn’t for a while. Then, the Parkinson’s just really started working at me.”

In April 2011, Long visited Emory for the first time. He arrived in the PD center in a wheelchair, but two days later, he walked out on his own.

How did the turnaround occur? An Emory physical therapist worked intensely with Long, teaching him to take bigger steps. He was told to imagine following a straight line, to concentrate solely on walking rather than trying to walk and talk simultaneously. And it worked.

Friends back home told Long that he looked better than he had in years. And his wife, Faye, says, “Jimmy’s clinic visit was like a turning point for him. We assumed that he was going to be in a wheelchair from here on out. We learned more in our visits with Dr. Factor and the clinic than we did in all the years prior to the visit.”

Emory’s center also tackles another common—but often overlooked—symptom of PD: depression. Although up to 60% of Parkinson’s patients experience some form of depression, patients often choose to suffer through it rather than seek treatment. However, more than being a reaction to having PD, depression can be caused by PD itself when the disease impacts brain chemicals such as serotonin and norepinephrine.

“We have patients who have never seen a psychiatrist and insist that they don’t need to see one,” says Emory research nurse and comprehensive care coordinator Mary Louise Weeks. “So having a psychiatrist at the center allows us to find those patients who might not have ever sought help on their own.”

Emory also connects families with a social worker, who can lead caregivers to additional resources for helping a loved one manage PD. The social worker also can help families deal with conflicting feelings they may encounter in providing support. “In the time that caregivers spend with our social worker, they often find acceptance and leave better equipped to take on their loved one,” Weeks says.

The two-day center visit wraps up with a visit with Factor, who, based on a review of the notes from all the specialists, creates a plan to best care for each patient. The treatment plan might include adjusting medications, making referrals, or offering suggestions for follow-up care.

“This type of integrated care shows us the whole patient,” he says. “It allows us to offer patients a comprehensive and personalized plan.”

Round 3: Going for the win

Beyond making a positive change in the everyday care and quality of life for PD patients, Emory’s movement disorders teams haven’t given up on the ultimate goal—finding a cure. And they are getting help from a variety of sources, including a recent $4 million boost for PD research from Jean and Paul Amos as well as a NIH-funded Morris K. Udall Center of Excellence for Parkinson’s Disease Research. At Emory’s Udall Center, more than 45 faculty are pursuing research in PD, from anatomy and electrophysiology to pharmacology and toxicology. The clinical work by Factor and others helps the researchers identify patients who might be good candidates for participation in clinical trials.

Merrie Boone, whose original motivation in supporting Emory was to help patients understand and cope better with PD, now is encouraged by the longterm benefit to the research program.

And in another attempt to connect researchers and PD patients, a new collaboration between Emory and the Wilkins Parkinson’s Foundation is producing “PD Research—Sounds from Emory.” The series of podcasts—funded by the Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute—will bring interviews with leading Emory PD researchers to a broad lay audience to disseminate relevant research findings in a timely manner on the foundation’s website. The podcasts will establish a more direct and personal link between Emory’s PD research program and the community.

Lonnie Ali hopes that all of these efforts will have a cumulative effect. “I believe with dedicated researchers, adequate funding, and well-equipped research facilities, our collective understanding of this disease will advance dramatically,” she says. Her wish not only for her husband but also for all PD patients is for better treatments that can improve their physical and mental health and increase their quality of life.

Additional ResourcesEmory would like to elevate the level of care of all patients with Parkinson’s disease by continuing to develop its comprehensive PD care center. If you would like to support that effort, contact Barry Steig at bsteig@emory.edu or call 404-727-9099. To learn more about research aimed at reversing motor symptoms and depression in Parkinson’s patients, contact Kathryn Graves at kgraves@emory.edu or call 404-727-3352. For info on PD research at Yerkes Primate Research Center, contact Margaret Lesesne at margaret.lesesne@emory.edu. To make an appointment with an Emory movement disorders specialist, call 404-778-3444. For general information on PD, see emoryhealthcare.org/neurosciences/conditions/parkinsons-disease.html. For the latest research information from the NIH, visit ninds.nih.gov/research/parkinsonsweb/udall_centers. To hear future podcasts of Emory researchers discussing new findings about PD, visit the Wilkins Parkinson’s Foundation at Wilkins-PF.org. |