Children and COVID-19

Pediatric cases of the novel coronavirus range from asymptomatic to a serious inflammatory syndrome. More is being learned with each new case. But the unknowns are still daunting, for families and doctors.

Hannah Friday doesn’t want to hear anyone say, “Kids don’t get sick from COVID.” In fact, it infuriates her.

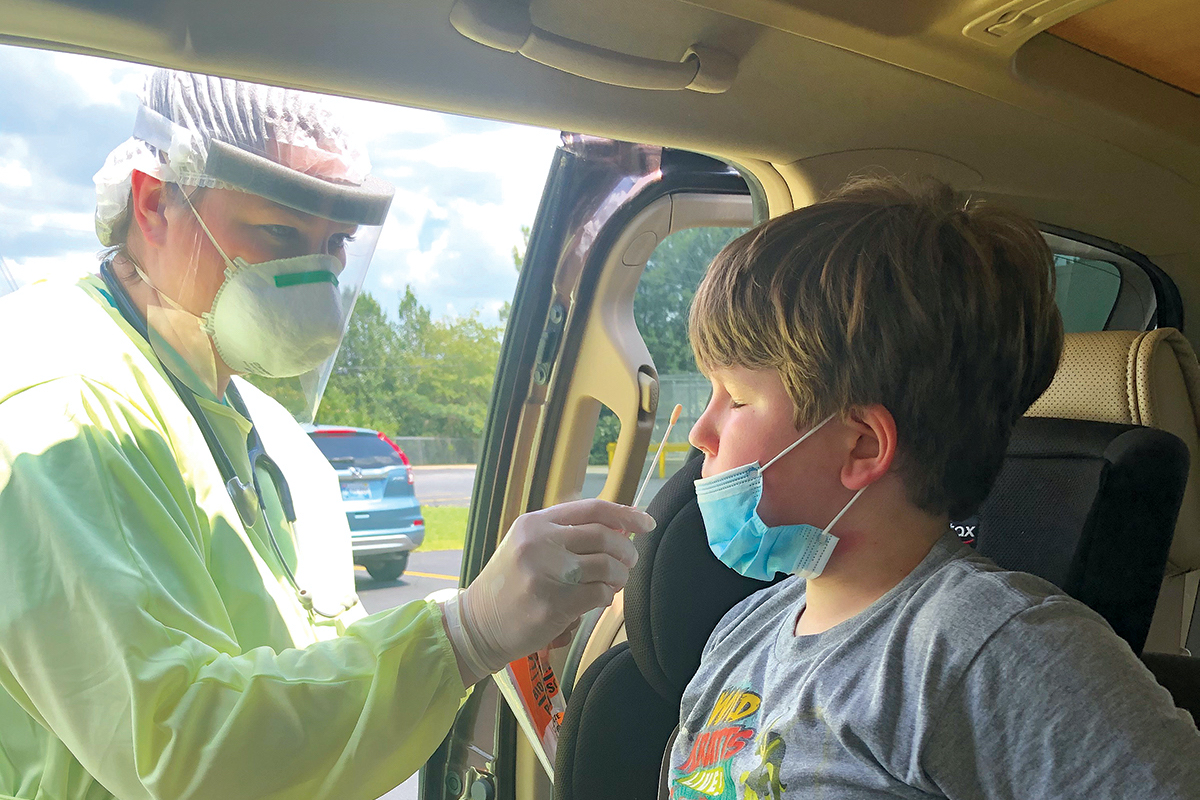

The pandemic hit home for Emory alumni Hannah and Patrick Friday and twin sons Clint and Sam (l-r, above, at Patrick's church in Birmingham) when Hannah and Sam tested positive for the virus.

That’s because she watched her son Sam suffer intensely from the virus.

“To have an 8-year-old beg you to take him to the hospital …” she says, her voice trailing off.

Patrick and Hannah Friday, both Emory Candler School of Theology alumni and former missionaries, live in Birmingham, Alabama, with their twins, Sam and Clinton, where Patrick leads a United Methodist church and Hannah is an adjunct professor at Beeson Divinity School at Samford University.

At the end of June, they took their son to their local ER with a severe stomachache, pain in the area of his spleen, and severe pain in his chest (“He said it was 10 out of 10 pain, for at least a week”). He was also dragging one of his legs behind him.

Initially, Sam was given two diagnoses: indigestion and constipation. “I had done research and knew he had symptoms that children get with COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C),” says Hannah. “I’m in a high-risk group and so I asked that the whole family be tested. Everyone we called said no, we’re not going to test you, just assume you have it and quarantine.”

The Patricks had been extremely careful, isolating and masking, with Hannah going grocery shopping every two weeks and Patrick switching to “drive-in” services at church.

“We only took the kids out three times,” Hannah says, but at one of those gatherings—a family funeral held outside at a farm—she believes they were exposed to the virus.

On July 1, Sam’s test came back positive. They were told to isolate Sam from the rest of the family. Instead, Hannah moved the boys into her room, with Sam sleeping on one side and Clint on the other.

“I couldn’t leave my 8-year-old son in his room and bring food to him,” Hannah says. “He was sleeping with me, I had him by my side.”

Finally, the entire family was tested, and this time Hannah tested positive for COVID-19 as well. “It was a relief to finally get the test and the results, actually.”

Sam “is our calm child, and if you looked at him, he looked healthy . . . but that wasn’t the case,” says his mom, Hannah Patrick, who also tested positive for COVID-19.

Hannah’s symptoms included a severe head-ache and chills that caused her to bundle up in heating pads and an electric blanket. She could feel the virus moving down into her lungs. “At my worst, I didn’t even have enough energy to walk outside,” says Hannah, who started intense self-care, including steam with eucalyptus, immune boosters, and over-the-counter medications. “I also had steroid inhalers and a nebulizer, as well as a pulse oximeter and blood pressure cuff at home.”

Patrick was worried and not sure what to do. “To see your child affected by COVID in such a mysterious way, and then your wife catches it,” he says. “It was pretty overwhelming.”

During the worst of his symptoms, Sam asked his parents, “Do you have to breathe in heaven?”

At the same time that her family was suffering, Hannah was seeing all the doubters on social media, people saying COVID was fake, children couldn’t get it, and there was no need for masks.

“No illness should be politicized,” she says. “I was actually questioned by people online, after we knew that Sam had it. I posted a photo of him in the hospital. People need to know it is real and children can get sick from it.”

COVID-19-related syndrome in children

Children can, indeed, get COVID-19, says Preeti Jaggi, associate professor of pediatric infectious diseases and a clinician at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. And while pediatric deaths from COVID are rare, and 94% of children’s cases are considered mild to moderate, some children can become seriously ill. Children with underlying medical conditions are particularly vulnerable.

“Kids can become ill from COVID requiring hospitalization, just not at the same rates as adults,” Jaggi says.

A subset of children who may have initially had very mild to undetectable illness can become critically ill. These are the ones suffering from COVID-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C.)

MIS-C is a condition where body parts can become inflamed, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, eyes, or gastrointestinal (GI) organs. As with the Fridays’ son Sam, one of the earliest symptoms can be GI distress, so the symptoms could be mistaken for a stomach bug, indigestion, or food poisoning.

“We do not yet know why some children develop MIS-C. MIS-C can be serious, even deadly, but most children who were diagnosed with this condition have gotten better with medical care,” reads the CDC site on MIS-C.

Symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, neck pain, a rash, bloodshot eyes, and feeling extremely tired.

“MIS-C was only identified on April 27, so basically clinical care and research started at the same time,” Jaggi says.

As well as caring for children with COVID and COVID-related illnesses at Emory Healthcare and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Jaggi and colleagues have been conducting studies as rapidly as they can collect data, hoping to find out more about pediatric transmission, manifestation, and treatments.

For example, in their study on “Burden of Illness in Households with SARS-CoV-2 Infected Children,” published in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, they investigated the dynamics of illness among household members of SARS-CoV-2 infected children who received medical care (sample size was 32 children who had tested positive for COVID-19).

“We identified 144 household contacts: 58 children and 86 adults. Forty-six percent of household contacts developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19 disease. Child-to-adult transmission was suspected in seven cases,” the authors said.

Jaggi has also been involved in studies to:

- describe the similarities and differences in the evaluation and treatment of MIS-C at hospitals in the United States, in the absence of evidence-based therapies for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

- measure SARS-CoV-2 serologic responses in children hospitalized with MIS-C compared to COVID-19, Kawasaki disease, and other hospitalized pediatric controls.

“Understanding the epidemiology and clinical course of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and its temporal association with COVID-19 is important, given the clinical and public health implications of the syndrome,” says Jaggi, who has seen about 30 to 40 children diagnosed with MIS-C.

Some children’s blood serum was stored and they were diagnosed retrospectively, she says.

Fraternal twins Sam and Clint enjoy outside time at home, where their family spent most of their time isolating during the pandemic.

Jaggi has long had a research interest in Kawasaki disease, an inflammation of the blood vessels that usually affects children younger than 5. At first, she and many other experts thought that’s what they were seeing in children with this type of severe inflammation, but “they were older than the norm—most were over 5 years of age and the median age was 9.”

And, unlike the normal adult symptoms of COVID-19, Jaggi and her fellow clinicians were seeing children who didn’t have respiratory symptoms or coughs, but presented with fever, gastrointestinal symptoms, and hypotension. “They were really sick, it was scary,” she says. “Some needed oxygen, their bellies were distended. There were cases of severe cardiac dysfunction.”

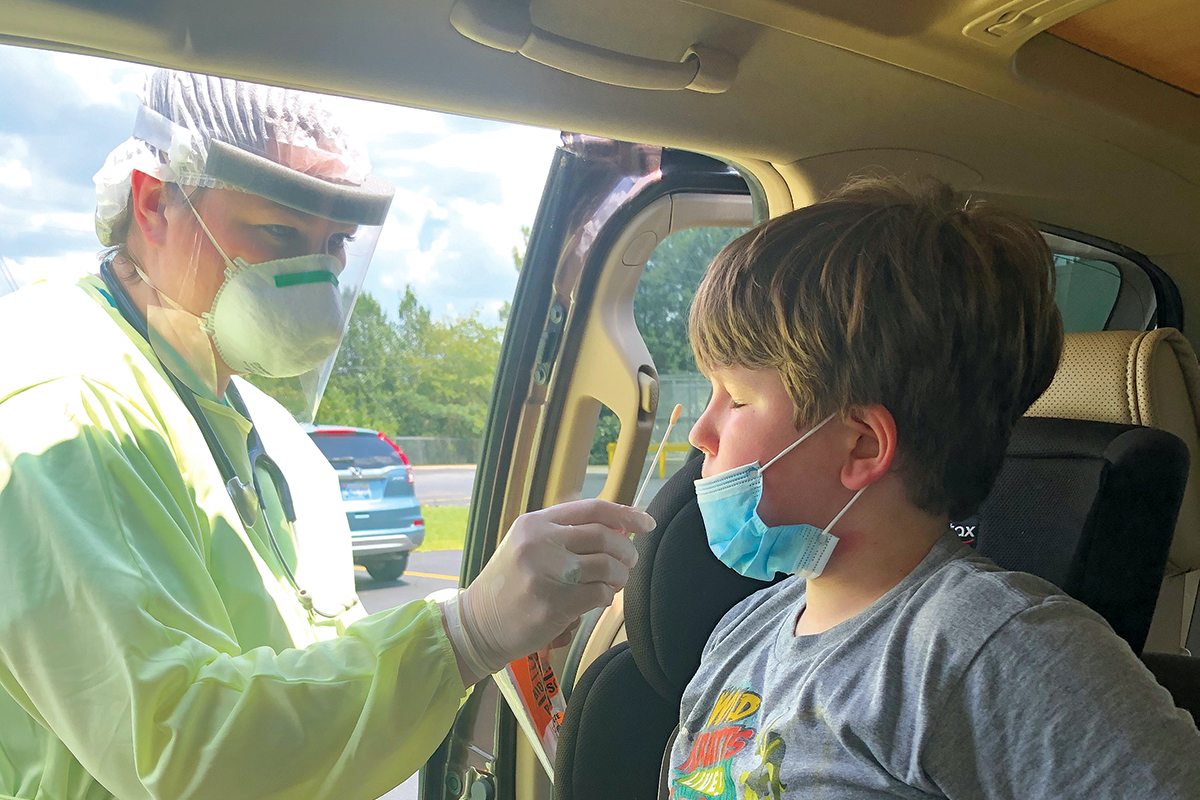

The belief now among the CDC and medical experts after studying cases nationwide, says Jaggi, is that MIS-C has two different phenotypes: “The first are children who do not test PCR-positive (by nasal or throat swab saliva tests) but are only identified through serologic testing, which probably means an old infection. Then there are the children who test positive from the swabs, and in that case, MIS-C overlaps with acute COVID.”

Some adults experience a lot of inflammation with COVID-19 as well, which is why the -C was added to the diagnosis, meaning specifically multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

And MIS-C is, by definition, serious: a child must be sick enough to have stayed in the hospital in general for about 48 hours to earn the diagnosis.

There may even be lingering cardiac issues. “We are tracking everything in these kids,” Jaggi says. “We are carefully monitoring their follow-up with specialists, like cardiology, to make sure they don’t have long-term issues with their hearts.”

The Fridays’ pediatrician told Patrick and Hannah the same about Sam—that he might have lingering effects from the virus.

The Fridays met at Emory, graduated from Candler School of Theology in 1998, married in 2000, and later found out they were having twins. They named them after two United Methodist ministers and missionaries who died in an earthquake in Haiti—Samuel and Clinton.

The twins are in no way identical—Sam is larger and steady; Clint is smaller and more dramatic. Where one goes, they both go, says their mom.

While caring for young patients with COVID-19, Emory and Children’s Healthcare pediatrician Preeti Jaggi and colleagues also have been conducting research on how the virus affects children.

So when Sam started complaining about his pain, his parents knew something serious was wrong. “He is our calm child and if you looked at him, he looked healthy. So even doctors were saying, ‘He’s fine, just take him home.’ But that wasn’t the case.”

Hannah and Patrick want to let other parents know that they need to be advocates for their children, especially with a new disease, like MIS-C, that even some of the medical workers they encountered had never heard of.

Hannah and Sam are feeling better, although they are both suffering some aftereffects. “My body has not quite regained its ability to regulate my temperature, and I am still having pretty severe joint pain,” she says. “Sam is starting to do a little exercise, including tennis practice.”

After Hannah told people that she and Sam had COVID, and posted a picture of him at the hospital on social media, other people started writing to her to let her know they or their family member had it too, she says: “A month later, everyone knew someone who had it.”

COVID-19 Helpers

A book to let children know ways they can help during the pandemic, by author Beth Bacon and illustrator Kary Lee, won the Emory Global Health Institute COVID-19 children's eBook competition, along with a $10,000 prize. The contest, which was aimed at providing information for 6-to-9 year olds, was proposed by Jeff Koplan, director of the institute and VP for Global Health at Emory, and inspired by his grandchildren's questions.

View the winning and runner-up books

The Paradox of COVID-Related Inflammation in Children

Measuring blood antibody levels against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, may distinguish children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), a serious but rare complication, say researchers at the School of Medicine and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

Children with MIS-C had significantly higher levels of antiviral antibodies—more than 10 times higher—compared with children with milder symptoms of COVID-19, the research team found. The results, published in the journal Pediatrics, could help doctors establish the diagnosis of MIS-C and figure out which children are likely to need extra anti-inflammatory treatments. Children with MIS-C often develop cardiac problems and low blood pressure, and require intensive care.

The high antibody levels may represent an exaggerated immune response or a delayed complication of COVID-19, or a combination of both, says Christina Rostad, assistant professor of pediatrics at Emory and an infectious disease specialist at Children’s. Senior author Preeti Jaggi, associate professor of pediatrics (infectious disease) at Emory School of Medicine and Children’s, says that “one of the challenges in interpreting these findings in children with MIS-C is that we do not know when they were actually infected with the virus. The rapid emergence of MIS-C has required physicians at Children’s and researchers at Emory to work collaboratively to quickly understand the clinical course of the disease, treatments, and pathophysiology and has required a huge team effort from clinicians and basic scientists.”

Children’s physicians have continued to see cases of COVID-19, and more than 50 cases of MIS-C have met the definition of MIS-C requiring hospitalization, in the Children’s Healthcare system. “These cases underscore the importance of all the efforts we are taking as a community to decrease transmission of this virus. By wearing a mask, washing your hands, and avoiding large gatherings, you may be saving someone’s life,” Rostad says.

Patients with MIS-C usually present with persistent fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and skin rashes, and severe cases have low blood pressure and shock, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How MIS-C develops remains mysterious. Recent reports have suggested that it arrives in a second wave of inflammation, after the initial viral infection. None of the children with MIS-C studied by the Emory and Children’s researchers recalled having a previous fever or respiratory illness, even though they had high levels of antiviral antibodies. However, the majority tested negative for an active infection at the point of their hospitalization.

The authors remark that it “seems paradoxical” that children without preceding symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection develop such intense immune responses. It may hint that although some children with active infections lack symptoms, they are still capable of developing robust immune responses. “These studies provide supportive evidence that MIS-C represents an aberrant immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children,” Rostad says. “However, the mechanisms of this disease process and the reasons some children develop symptoms while others don’t remain areas of active research.”

When they first came to the hospital, children with MIS-C mainly displayed gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms. Several of them developed myocardial dysfunction with decreased ejection fraction—a measure of the heart’s ability to pump blood. All patients with MIS-C needed to be hospitalized in intensive care because of low blood pressure.

Between March and May 2020, the researchers studied 10 children hospitalized with MIS-C, 10 with symptomatic COVID-19, five with Kawasaki disease, and four hospitalized “control cases.” Kawasaki disease is a pediatric inflammatory disease affecting blood vessels, including the coronary arteries, which shares some features with MIS-C. The average age of the children with MIS-C was 8.5 years.

The time elapsed between symptom onset and antibody samples being taken varied, generally between zero and 20 days, with a few in the MIS-C group later than 20 days. The researchers used tests for antibodies against the receptor binding-domain of the viral spike protein and the viral nucleocapsid protein using assays developed in the laboratory of coauthor Jens Wrammert, assistant professor of microbiology and immunology. They also performed live-virus neutralization assays in the laboratory of coauthor Mehul Suthar, assistant professor of pediatrics.

The children with MIS-C were treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (a mixture of donated antibodies) and half received corticosteroids, a common anti-inflammatory medication. Some of the COVID-19 group were treated with antiviral or immunomodulatory drugs such as remdesivir (four) and convalescent plasma (two).

All the children with MIS-C eventually returned home. Two of the patients with symptomatic COVID-19 were being treated for leukemia and died due to their underlying disease.

—Quinn Eastman