News and views

![]()

Connecting the dots

By Pam Auchmutey and Martha McKenzie

Peter Ehrenkranz’s first brush with global health occurred after his junior year in college when he biked his way through Zimbabwe to learn about its hospital system.

Ehrenkranz 02M/MPH was impressed by the ingenuity of health workers in Zimbabwe, including a doctor who discovered that a child’s insulin could be kept cool by storing it in a clay pot buried in the ground. “Doctors in places like Zimbabwe have to think outside of the box,” says Ehrenkranz. That premise has been the bedrock of his career, which has included seven years working in Liberia and Swaziland to reduce incidence of HIV and tuberculosis and strengthen health systems.

Last year, he moved with his family to Seattle to serve as senior program officer for HIV treatment with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the fifth-largest funder of HIV initiatives globally. “It’s a great opportunity to take some of the lessons I learned in the field and apply them to a bigger policy sphere,” says Ehrenkranz. “I’m trying to help move countries with high burdens of disease as well as funders who are even bigger than us—including the U.S. government—to be as innovative as possible. We’re trying to use our funds to answer the questions that are going to be priorities three years from now. In a fast-moving field like HIV, we have to be agile.”

As an MD/MPH student at Emory, Ehrenkranz learned to strike a balance between caring for individual patients and improving health services delivery overall. After completing his medical training, he joined the Clinton Health Access Initiative as the senior technical adviser to the National AIDS and STI Control Program in Liberia. He saw patients once a week in clinic, where he helped identify the country’s first cases of drug-resistant tuberculosis—which often affects HIV patients—and worked with the government to procure the recommended drugs for treatment. He also collaborated with program staff to write the nation’s first HIV guidelines, train health workers, build a national public health reference laboratory, and create a sustainable drug supply chain. “In Liberia,” he says, “we were drawing the dots, not connecting the dots.”

In Swaziland, where he served with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as the HIV care and treatment team lead and then country director, he partnered with the Ministry of Health to increase the proportion of people eligible for HIV treatment from 60 percent to more than 90 percent. After one year, more than 80 percent remained in treatment and had a suppressed viral load. “The viral load measures are equal to or better than those in the U.S. There was great leadership on their side,” Ehrenkranz says. While there, he developed an interest in quality management and helped draft the quality and assurance guidelines adopted by the Ministry of Health to address HIV and TB prevalence rates—the highest in the world. He also supported the office in replicating a program from Liberia that brought county and central ministry health leaders together to present progress on key indicators, share ideas about what did and did not work, and increase accountability among all parties for delivering health care. In the Swaziland version, a sense of competition evolved among doctors at the biannual meetings where they received awards for successes, including most improved, best retention in care, and most innovative programs. “They still get together twice a year,” Ehrenkranz says.

At the Gates Foundation, he is expanding these peer networks to other countries to boost access to and quality of HIV prevention and treatment. Given that expected changes in World Health Organization guidelines will essentially declare that all people living with HIV are eligible to start treatment, the world soon will be asked to double the number of people receiving antiretroviral drugs with little change in the resources available to do so. The only way forward is to develop new models of service delivery that are less burdensome on health care systems and patients. That includes introducing new ways of testing and treating patients in clinics and hospitals and working with funders and agencies to provide patients with easier access to drugs.

Where in the world are you?

From Addis Ababa to Chaco, Bolivia

The daughter of two physicians from Macon, as a child Jennifer Spicer didn’t believe she would ever enter the medical field because of her tendency to faint when she received shots at the pediatrician’s office.

But she fell in love with microbiology at the University of Georgia, which led her to enter Emory’s School of Medicine in 2007.

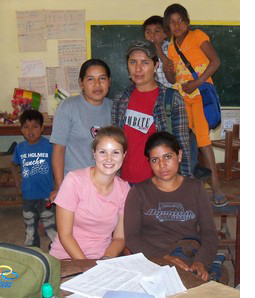

She received a 2011 Kean Fellowship that allowed her to work abroad in Bolivia, where she helped set up a field site in the Chaco region. “We had to overcome distrust in the Guarani communities where other projects had failed to follow through on their promises,” she says. “Even though we had many long, challenging days, I found that I loved every minute of it.”

Then, during her internal medicine residency, Spicer 12M/MPH completed a clinical rotation at Black Lion Hospital, which served patients who couldn’t afford care in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Spicer spent a month there teaching residents about infectious diseases as part of the Emory Global Health Residency Scholars Program. She spent mornings in the HIV clinic and afternoons doing inpatient consults. “I was in Ethiopia with an infectious diseases fellow and attending from Emory,” Spicer says. “Every day we either led an informal case discussion, visited the microbiology lab, or delivered a lecture.”

The experience informs her current work as chief resident in internal medicine at Grady Hospital. “Even though they have limited access to textbooks, journals, and the Internet, the residents [at Black Lion] had a tremendous fund of knowledge, which surpassed my own expertise in many areas,” Spicer says. “It was great to be able to learn from each other.”—Pam Auchmutey

![]()

Are you doing interesting work in, say, rural Kentucky, New York City, Jakarta, or Taipei? Let us know where you are and what you’re doing with a quick email (and photo!) to the editor: mary.loftus@emory.edu.