A Champion for Children with Developmental Disabilities

By Pam Auchmutey

Marshalyn Yeargin-Allsopp 72M

5 THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT

|

At some point each day, Marshalyn Yeargin-Allsopp 72M thinks of her late mother. Yeargin-Allsopp was eight years old when her mother had surgery for a dissecting aneurysm on Mother’s Day in the mid-1950s.

“She was the first patient to survive the surgery at Vanderbilt Medical Center,” the daughter recalls. “I wrote a letter to her physician and thanked him for saving my mother’s life.”

Several years later, her mother had the surgery again but did not survive. Yeargin-Allsopp, then 17, was devastated.

“I cried every day for many years,” she says. “But I came to reflect that she could have died when I was 8 years old. She lived another nine years thanks to the skill of her physician.”

The experience strengthened Yeargin-Allsopp’s own resolve to practice medicine. “I knew at a young age that I wanted to be a baby doctor. I don’t know where that desire came from, but it was always there.”

Yeargin-Allsopp grew up in Greenville, South Carolina. In 1964, at age 16, she entered college in North Carolina but transferred a year later to Sweet Briar College in Virginia, a women’s college with a strong science department. Her great uncle, Benjamin Mays, then president of Morehouse College in Atlanta, recommended Sweet Briar as one of the few Southern schools that might be accepting black students.

Yeargin-Allsopp didn’t know she would be the first black student at Sweet Briar until she began receiving calls from newspaper reporters. She overcame the publicity to concentrate on her studies in biology and chemistry in preparation for medical school. Though the curriculum tested her, she excelled and in 1968 became the first black female to enter Emory School of Medicine. Of the 80 students in her class, eight were female and four were black.

“The three black males were like brothers to me—we were constant companions,” Yeargin-Allsopp says. “Three of the women became my roommates.”

Her classmates and her Uncle “Bennie” lifted her spirits whenever she became discouraged. “Medical school was tough, as most people describe it,” she says. “But it was well worth it. Medicine was my lifelong dream.”

She subsequently trained in pediatrics at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx, New York. During her residency, she worked in a health clinic for low-income residents and came to know families well. Many had concerns about child behavioral and emotional issues, leading Yeargin-Allsopp to complete a fellowship in developmental pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and with the United Cerebral Palsy Research and Educational Foundation.

Married with her first baby, Yeargin-Allsopp set her sights on moving back South after her fellowship. She convinced her New York-born-and-bred husband to move to Atlanta, where she joined the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service in 1981. She was assigned to the birth defects branch and put in charge of a new project to develop surveillance on children with developmental disabilities.

“I wasn’t sure if the CDC would be a good fit because I was a clinician,” says Yeargin-Allsopp, now a senior medical officer with the Division of Human Development and Disability. “Thirty-eight years later, I’m still here.

In that time, she has pioneered research to understand the prevalence of autism and other conditions. In 2003, Yeargin-Allsopp was

Yeargin-Allsopp’s study led to

|

|

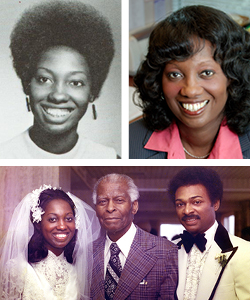

| Marshalyn Yeargin-Allsopp (counterclockwise, from top left) in medical school at Emory, where she was the first black female student to enter, at her wedding to Ralph Allsopp, and at the Clayton Early Intervention Program. | |

Researchers have yet to understand why ASD is increasingly prevalent. While early studies showed that about two-thirds of children with ASD had intellectual disability, more recent studies indicate that almost 50 percent of these children have average to above average intelligence. ASD is more prevalent among white children compared with black and Hispanic children. The obvious question is why.

“Autism is not one entity,” says Yeargin-Allsopp. “It has different clinical and behavioral presentations, and the ability to communicate, learn, think, and problem-solve varies from child to child. Research has led to the understanding that there is no one cause, suggesting that genetics and environmental factors play a role. We do know that early screening and intervention is key to helping children thrive.”

Yeargin-Allsopp is an adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics at Emory’s School of Medicine.

Also, for more than 25 years, the CDC researcher served as medical director of the Clayton Early Intervention Program just south of Atlanta. “It allowed me to continue seeing children and talking with parents,” she says. “I learned so much from them. When we talk about numbers in population studies, behind each of those numbers is a ‘one,’ which may have been a patient I saw.”