Lessons from a previous outbreak

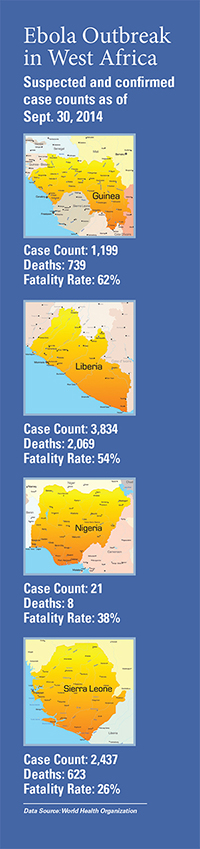

Vice President for Global Health Jeff Koplan, former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), oversaw the CDC’s response to previous Ebola outbreaks in Africa during his tenure as director from 1998 to 2002. He shares his thoughts about the treatment of Americans with Ebola at Emory University Hospital and the current outbreak in West Africa. Data Source for maps: World Health Organization

|

Creating the isolation unit at Emory University Hospital 12 years ago, through a CDC grant:

The initial thought was to have it available for CDC staff who might be exposed to pathogens in the lab or while working out in the field. When you have colleagues who are putting themselves at risk, you do what you can to minimize that risk and be prepared for any untoward events that might occur. There are four such isolation units in the country now, and all four are in proximity to institutions working with biosafety level 4 agents and the increased risk associated with that.

The selection of Emory University Hospital:

It was a first-rate institution close by. There's also been a long, close working relationship between Emory and the CDC, especially with Emory's Department of Microbiology and the Division of Infectious Diseases in the Department of Medicine. Many CDC staff trained at Emory, and many Emory infectious disease staff have spent time at the CDC. A large number of CDC staff serve as adjunct faculty at Emory.

Whether all major hospitals should build similar isolation units:

Probably not, but all hospitals should think about what they would do if they have a patient present with infectious disease symptoms. Where they would put them, airflow, etc. Regarding space allocation for hospital beds, you have to balance out the practical aspects of hospital needs—the rare vs. the day to day.

Why the current Ebola outbreak is so much worse than previous outbreaks:

The countries have changed, it's 13 years later, there is more development and better roads, people have more means of transport and more business dealings. It's one of the rare downsides of progress and development, that diseases are more readily transmitted over longer distances, to urban and more densely populated areas.

Best way to contain the outbreak in Africa:

Old-fashioned, tried-and-true public health practices—case identification, isolation, contact tracing, close observation and more isolation, watching contacts for symptoms. And finding every contact—not just every case, but every contact. You can't miss anyone, 85% is not enough, "most" isn't enough.

|

Koplan as an EIS officer at the CDC in the 1970s, working on smallpox eradication efforts in Bangladesh. |

|

Why people are so afraid of an Ebola outbreak here:

Ebola has received a fair amount of publicity even before this outbreak. People see it as the epitome of the 21st century plague, even without zombies helping it along. Movies have played up this fear. But now, we aren't trying to promulgate fear, we're taking a rational, thoughtful approach that's at odds with what the public has seen and heard for 15 years in movies like Outbreak, Contagion, etc. Ebola is scary and has been portrayed in its scariest light, so that fear is understandable.

Treating the two Americans with Ebola:

We have a very good hospital here, and it exists to care for ill persons. If these were US soldiers, would we say, "no, you can't return home for care?" These are missionaries, soldiers in their own way for peace and health, our countrymen who were trying to make the world a better place. They deserve to be treated with compassion and the best health care we can offer when they want to come back home.