Hiding in Plain Sight

By Mary Loftus

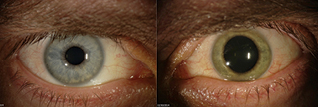

Dr. Steven Yeh checks Ian Crozier's left eye at a follow-up appointment in June. Crozier developed severe vision loss months after he recovered from a near-fatal Ebola infection. During testing, live Ebola virus was found inside Crozier’s eye. Jack Kearse

When his vision started to deteriorate, it was a devastating blow to Ian Crozier, a 44-year-old doctor infected with the Ebola virus while treating patients in Sierra Leone at the height of the epidemic in the summer of 2014.

After being diagnosed in early September, Crozier was flown back to the United States and spent "40 days and 40 nights" in Emory University Hospital's Serious Communicable Diseases Unit. He remembers little of the first weeks of his stay, beyond his few steps from the ambulance to the unit in full protective gear.

|

|

He was by far the sickest Ebola patient Emory doctors had cared for. After experiencing multiorgan failure, he had been placed on a ventilator for several weeks to help him breathe and underwent kidney dialysis to clear toxins from his body.

The general dogma at the time was that if Ebola patients needed dialysis or a vent, they would invariably die," says Bruce Ribner, medical director of the unit. "This changed the algorithm for how aggressive we could be."

Slowly, Crozier had come back to himself. He was found to be virus free and was discharged on Oct. 19. He traveled to his family's home in Phoenix to recuperate from fatigue and deconditioning, like an astronaut returning from a long journey. But the virus had another surprise in store. In December, Ebola was found hiding inside his eye, an alien stowaway that wasn't quite willing to give up its host just yet. "It felt personal, that the Ebola virus could still be in my eye without my knowing it," he says.

|

|

Crozier's own story began in what is now Zimbabwe, where he was born and spent his childhood years. A place nourished by the Zambezi River, it was home to hippos and rhinos and boyhood adventures, but also to years of a protracted war leading to the country's independence in 1980. His family moved to the U.S. when Ian was 10, and he went on to graduate from medical school at Vanderbilt, later training in internal medicine and infectious diseases.

Feeling drawn back to Africa, Crozier was living in Uganda, caring for HIV patients and training physicians, when the Ebola outbreak occurred. He volunteered with the World Health Organization (WHO) to go to West Africa, where he was assigned to the Ebola Treatment Unit in Kenema, Sierra Leone. One of the unit's main doctors had just died of the virus, and Crozier joined a staff already long overwhelmed by unexpected volumes of patients as the virus spread throughout the country.

Ebola is not a tidy disease—blood, vomit, and diarrhea are ever-present and tending to the ill in full protective gear is hot, exhausting work. In the middle of so much death and suffering, Crozier noted a remarkable fortitude in local health care workers and in patients and families. "Childless parents took care of parentless children," he told The New York Times.

Local and foreign health care workers alike were being infected at an alarming rate. "Ebola kills thrice: first the patient, then the patient's closest caretakers (family), then the doctors and nurses," Crozier says. "It leads to multiplied devastation."

He sent home a young nurse from England who was infected—William Pooley—on a medical evacuation flight, and wryly joked with the flight crew later that he didn't want to see them again.

In early September, Crozier developed a fever and headache, and drew his own blood for a diagnostic test. It was positive for Ebola. On Sept. 9, he was flown to Emory University Hospital, where he was admitted to the Serious Communicable Diseases Unit. "I would have been dead in a week had I not been evacuated, and for that I'm incredibly grateful," says Crozier. "I have to hold that gratitude in tension with the present awareness that many of my patients, some of my colleagues, and a few of my friends were not afforded the same opportunity and died in Kenema."

Crozier was Emory's third Ebola patient, taking over the room recently vacated by Dr. Kent Brantly, who had acquired the virus while caring for patients in Liberia. Crozier's family kept his identity confidential, so he was known only as "Patient 3" outside the unit.

Since no "cure" exists for Ebola, the infectious disease team concentrated on providing supportive care, trying to keep Crozier alive long enough for his own body to battle back the disease.

The only therapeutic weapons available were plasma from Ebola survivors' blood and experimental antivirals—but no clinical trials had been done on what actually worked, how much to give, or what combination of the two would be most effective.

English nurse Pooley, whom Crozier had seen off, flew to Atlanta to donate his blood so that his "survivor plasma" could be given to Crozier. (The plasma of Ebola survivors is now being banked at Emory.)

As Emory doctors and nurses were discovering, "best practices" for the clinical care of Ebola patients were often a guessing game. Crozier was an ideal teaching case, though, precisely because he was so ill. When he arrived at Emory, his blood had 100 times the viral load of any previous patient. "I want to make sure that what was learned at my bedside, and at the bedside of the other survivors at Emory, is translated and applied to a West African setting," he says.

|

|

After his recovery and discharge, he began hearing that fellow survivors in Kenema were struggling with post-Ebola ailments. Several common symptoms kept popping up: profound and disabling fatigue, severe joint and muscle pain, headaches, short-term memory loss and other neurocognitive problems, and vision problems.

Crozier was surprised to hear that 30 to 40 percent of survivors were having eye problems. "That made me pay attention to a very mild burning I was having in both eyes, and a bit of light sensitivity and difficulty seeing things when I was reading or looking at my phone," he says. Since he was returning to Emory regularly for follow-up care, he mentioned this to his doctor, infectious disease specialist Jay Varkey, who referred him to ophthalmologist Steven Yeh at the Emory Eye Center.

In November, Yeh examined Crozier's eye and saw nothing out of the ordinary at first. But a look through dilated pupils to the back of the eye showed slight, strange scars in the periphery. "Somebody in their 40s shouldn't have these scars," says Yeh, "so we performed a fluorescein angiogram—a dye test that allows us to look at the physiology of the blood vessels and the optic nerve—and he did have some unusual abnormalities."

Then, in December, Crozier developed severe left eye pain, a left-sided headache, and nausea. He was walking back to his Atlanta hotel room one night when he noticed halos around the streetlights. He contacted Yeh who, with ophthalmology resident Jessica Shantha, met him at 11 p.m. at the clinic. They found that the pressure in his eye, which normally should be between 10 to 20 millimeters of mercury, was very high—44 mmHg. Yeh noticed inflammation in the anterior portion of the eye, signifying uveitis, which can cause blindness if left untreated. Over the next few days, the inflammation got worse, as did Crozier's vision. They began to believe that the aggressive uveitis was associated with Ebola. "Ebola and uveitis do have this very loose association," says Yeh. "Uveitus was observed in survivors of the 1990s outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo."

|

|

Using a hair-thin needle, Yeh took a sample of fluid (aqueous humor) from the anterior chamber of Crozier's eye.

Survivors are cautioned that the virus might still lurk in a few isolated, immune-protected parts of their body, such as the testes (and so are urged to use protection when having sex). But no one expected to find live, viable virus in Crozier's eye months after his blood had cleared. Just before the procedure, Crozier turned to the small group in the room and said, "This is not going to be Ebola, but just in case it is remember what it feels like to be right in the middle of a paradigm shift."

A few hours later, the rapid molecular test came back positive. At first, everyone was in shock. The eye care team consulted with the infectious disease team, then thoroughly decontaminated the exam room and informed others at the eye center.

The next day, a more comprehensive test showed that Crozier's eye fluid "wasn't just positive for Ebola but was positive at levels that were even higher than they had been in my blood," says Crozier. "And the levels in my blood had been orders of magnitude higher than any other of the U.S. survivors, at least to that point."

In fact, Crozier's left eye was teeming with Ebola—and not just pieces of dead virus or antigen, but viable, active, replicating virus. "After everything that I'd been through, it was still there," he says.

The team quickly swabbed and tested the surface of Crozier's eye and his tears, but no virus was present. This meant that he was not a risk for casual transmission or transmission to his family, since the virus was active only deep within his eye.

Yeh, who had been wearing gloves, a gown, and a mask when he did the sampling, nevertheless voluntarily isolated himself at home, sleeping in the guest room and separating himself from his wife and infant son for the incubation period of 21 days.

Meanwhile, Crozier's sight was deteriorating at an alarming rate. Worse yet, the usual treatment for uveitis—steroids—has the potential to make a viral infection like Ebola explode. The team decided it had to treat the eye to save it, however, and progressed from topical cortical steroids to oral steroids as the severity of inflammation worsened.

By the end of the year, Crozier could only sense hand motions with his left eye and was wearing a patch over it much of the time. Then the pressure in his eye normalized—and continued dropping until it was nearly undetectable, which was also very worrisome. "Your eye should feel like a hard-boiled egg to the touch. That's normal pressure," Crozier says. "Mine began to soften, and we noticed it was losing some of its architecture."

Crozier was admitted on Christmas Eve to the very bed in the isolation unit that he had left in October. His brother stayed with him, trying to bring some holiday cheer, but there wasn't much to be had. The vision in his eye had decreased from a baseline of 20/15 (better than perfect) to what was considered legally blind over a span of just a few weeks. "It was a very dark December," Crozier says. "I was convinced I had lost the sight in the eye permanently."

During this period, he awoke one morning, looked in the mirror, and realized his left eye had changed from blue to green. (Infrequently, viruses can cause this.) "This felt like an increasingly personal attack, as the virus stole both my sight and my eye color," he says.

After taking a course of an experimental antiviral drug, Crozier realized that if he moved his eye up and down he could create a kind of portal—a "wormhole," he started calling it—through which he could see. It was a good sign, the beginning of regaining his vision.

"Ian's case was, I would say, easily the most complex and challenging one I've ever had," Yeh says. "What exactly worked, I think we're still sorting out."

Crozier was eager to take on the roles of clinician, researcher, and healer again. "I sit here, alive first of all, and looking through two eyes, which is absolutely remarkable for me personally," he says. "But there are 10,000 to 15,000 Ebola survivors in West Africa who are grappling with these ailments as well."

Drs. Yeh, Shantha, and Varkey, who had bonded with each other and Crozier as his case progressed, also were curious to see if the care Crozier received could be translated for use in Africa, to prevent other Ebola survivors from going blind.

"It could be that I'm an outlier of sorts and, because my acute illness was so severe it probably should have killed me, I may have some odd manifestations of the virus," Crozier says.

To learn more, a team led by Yeh, including Shantha, Crozier, and oculoplastic surgeon Brent Hayek, went to West Africa in early April. They took donated eye exam equipment—slit lamps and indirect opthalmoscopes and vision test cards—and flew to Liberia for a week, setting up in an outpatient clinic at ELWA Hospital in Monrovia.

They saw about 100 survivors. Some had uveitis, others had cataracts, dry eyes, or glaucoma. (They didn't test for Ebola, due to exposure risk.)

The doctors taught the local staff how to check ocular vitals and detect uveitis, which needs to be treated quickly and aggressively, says Yeh.

The hope is to develop protocols for the diagnosis and treatment of Ebola survivors with vision problems. "Visiting Liberia, it touches you," says Shantha. "It motivates you to do more."

Varkey, Shantha, Yeh, Crozier, and other colleagues coauthored a report about Crozier's eye condition that ran in the May 7 online issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, "Persistence of Ebola Virus in Ocular Fluid during Convalescence."

It concludes: "This case highlights an important complication of Ebola Virus Disease with major implications for both individual and public health that are immediately relevant to the ongoing West African outbreak."

The team was especially moved by a survivor who, after losing her husband, father, and two children to Ebola, was now losing her vision in both eyes. "How much," asked Crozier, "does this virus take from us?"

Video

Related Resources

"Emory Eye Center team makes second trip to West Africa in 'Quiet Eye' project" (8/31/2015)

"Ebola virus can persist for months within survivors' eyes" (5/7/2015)