Spin Doctor

By Patrick Adams and Mary Loftus, Illustrations by Andrew Baker

|

|

| Drs. Kimberly Manning and Alanna Stone |

“You okay, doc?

“Who me?” I pointed at my chest.

“Yeah, you.”

I turned my head away from the television and back toward him. I poked out my lip and furrowed my brow.

“Look like you got something heavy on your soul.”

Heavy on my soul. I didn’t say anything.

“I’m okay,” I finally said, speaking quietly. “But yes. That’s a good way to put it.”

I wanted to tell him. I wanted to tell my patient all about what was weighing me down.

But I was his doctor. So when he asked, I just stayed silent.

As soon as I got out of there, I turned my forehead into the nearest wall and let myself cry.

I could feel the people looking at me as they walked by, their feet slowing down and wondering what could be going on with this doctor and the muffled, guttural sounds she was making. No one said anything.

Maybe my actions spoke enough. I mean, whatever it was had to be awful.

A doctor facing a wall with shoulders shaking and body heaving in a stiff white coat said plenty.

—Dr. Kimberly Manning’s blog, “Reflections of a Grady Doctor”

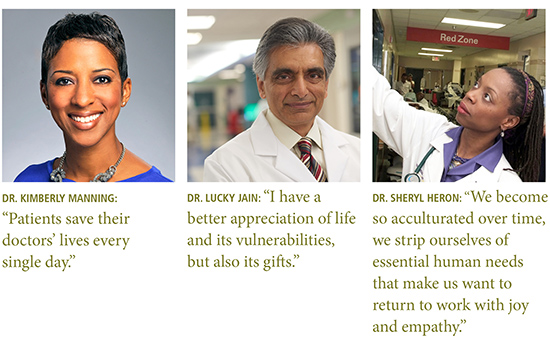

Kimberly Manning is a hospitalist at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, an associate professor of medicine at Emory, and an adviser in the

Her interests include humanism in medicine and the use of reflective writing. She practices what she preaches by writing a blog about her experiences at Grady. “I write to share the human aspects of medicine and teaching and work-life balance,” Manning says, “and to honor the public hospital and her patients, but never at the expense of patient privacy or dignity.”

She also writes about her frustrations and ways that she stays energized and optimistic in the face of daunting amounts of human tragedy.

Usually, she copes very well, finding joy in the job on most days. This is not a story about one of those days.

Manning first came to know Alanna Stone when Stone was a medical student in her small group of

After months of staying hopeful, Manning got the news that Stone had taken a turn for the worse and wasn’t going to make it. Unable to hide her preoccupation from one of her patients, Manning shared the basics of what was happening and left the room before bursting into tears. Crying in the hallway, she admits, “is not in the physician playbook.”

“I was crying because I would miss seeing the life of this beautiful woman continuing to unfold,” Manning wrote in her blog. “I was crying because 34 is too young to die. Crying because a little boy had lost his mother and a husband had lost his wife. Crying because one of the most epic students-turned-doctors that I have ever witnessed has had her career cut

Take Action

Physicians are, of course, human. They experience sadness and fear, illness and loss, anxiety and depression. They get overwhelmed, overloaded, and overextended.

But something has changed. Physician burnout is at an all-time high, with more than half of physicians saying they experience symptoms: emotional exhaustion, a loss of meaning in work, a sense of ineffectiveness, or a lack of engagement with patients. This represents a 25 percent increase over the past four years and cuts across physician gender, age, and ethnicity.

But something has changed. Physician burnout is at an all-time high, with more than half of physicians saying they experience symptoms: emotional exhaustion, a loss of meaning in work, a sense of ineffectiveness, or a lack of engagement with patients. This represents a 25 percent increase over the past four years and cuts across physician gender, age, and ethnicity.

On any given day, 30 percent of physicians say they feel stressed out, and 39 percent feel depressed. Such feelings can be fatal. Every year, about 400 physicians die by suicide. Many of them had not sought treatment or professional help beforehand, telling friends and family they feared it could have a negative impact on their careers.

“The day they start school, medical students actually are happier and better adjusted than their education-comparable peers,” says Philip Shayne, professor of emergency medicine and assistant dean for Graduate Medical Education (GME) at Emory School of Medicine. “Then there’s this big rise in burnout and depression that continues into their 50s.”

The American Medical Association calls physician burnout a “matter of absolute urgency,” and has issued a call to action. What accounts for this epidemic, and what can be done to combat it? Quite a lot, it turns out.

How physicians and the institutions that train and employ them deal with these stressors—in community or isolation, with support or silence—is proving to be a powerful predictor.

Physicians say their top stressors are bureaucratic tasks, heavy workload, computerization, and feeling like “a cog in the wheel.”

Privately, they share stories of patients lost, violence witnessed, childhoods shattered, and families reeling.

Not to mention the fear of making a mistake. “The system depends on individual infallibility,” says Emory hospitalist Anna Austin Von. “How we as physicians deal with that expectation is very much in the closet.”

Tait Shanafelt, chief wellness officer at Stanford Medicine who spoke at Emory’s annual medical education day in March, says a “blame the victim” mentality is pervasive in the field. “We tell physicians to get more sleep, eat granola, do yoga, and take better care of yourself. These efforts are well intentioned. The message to physicians, however, is that you are the problem and you need to toughen up.”

Instead, he says, academic health centers, hospitals, medical schools, clinical practices, and other institutions that train, hire, and rely on physicians must take the lead by focusing on change within the organization, culture, and system from the top down.

Proven antidotes to burnout include promoting autonomy, creating a sense of collegiality and community, and allowing time for meaningful work. “An individual organization that is committed to this at the highest level of leadership, and that invests in well-designed interventions, can move the needle and run counter to the national trend,” Shanafelt says.

Teach Self-care

Emory’s GME program, under the leadership of Shayne and Associate Dean Maria Aaron, has 104 specialties with 1,292 residents, making it the seventh-largest GME program in the country.

Shayne remembers his own experiences, first at Chicago’s Cook County Hospital, where he trained in one of the country’s busiest trauma units, and later at Emory, that led him to become an advocate for physician wellness.

“In the beginning of my career, I didn’t know how to process things,” he says. “You think you’re just supposed to be tough and that it’s not supposed to affect you. But those images—there was this one little boy I remember with a bullet wound to the head—they stay with you. To this day, those are the things that haunt me.”

During his 17-year tenure as program director for emergency medicine, Shayne took pains to engage in personal interactions with his 60-some residents. “One of the great things about training at Emory is that you get these incredibly diverse sites, which means you see a lot of very sick patients,” he says. “But it also means you’re being exposed to the things that we think cause burnout. Emory’s medical students and residents see a lot of really bad stuff.”

Wherever possible, Shayne tries to intervene. “I found that if you take a moment to pull residents aside and talk to them, they start processing in a way they hadn’t realized they need to. They learn to reflect and grieve.”

Physician training programs nationally are now required to provide residents access to confidential, affordable health care, including counseling and urgent care, 24/7. The new guidelines also urge improved interactions between residents and

All Emory residents were asked in late June to participate in the first-ever “burnout survey” conducted on campus. “We know what the numbers are nationally, but we don’t know what they are here, so we’re collecting data that will give us a baseline for future comparison,” Shayne says.

Residents need to know that help is available and confidential. “We’re lucky here,” he says. “We have a really supportive administration and faculty, and with the faculty staff assistance program (FSAP), we have the Rolls Royce of support services.” FSAP offers one-on-one counseling, group workshops, and other wellness services for Emory faculty and staff. “It’s free, it’s anonymous, and it’s offsite, so nobody sees you going in or out. They’ll even make accommodations for extra hours.”

Still, telling residents about available resources is one thing; making sure they hear that message is another. Medical students and residents tend to be high performers driven to perfection, Shayne says. “They didn’t get where they are by accident. You have to show them that this is not punitive and that the resources really can help.”

Von, a hospitalist at the Atlanta VA Medical Center, remembers vividly the anxiety she felt throughout medical school at Emory. “The weight of the responsibility of caring for other people became paralyzing,” she says. “During my sub-internship, I would call my husband crying every time I walked out of the hospital.”

Then came the morning that she had rounds at Hughes Spalding and was put in charge of an infant’s care. A nurse reminded her to put up the

Pay Attention

Even when physicians think they are managing just fine, stress may be taking a silent toll. Six years ago, Lucky Jain was at the peak of his career. A tenured professor of pediatrics with a well-funded lab and prestigious academic

Then one morning, at a national medical meeting in Orlando, he collapsed as he was walking to the podium to speak, felled by a major heart attack.

Colleagues resuscitated Jain on the spot, performing chest compressions until an ambulance arrived. Minutes later, he was rushed to a local hospital where an Emory-trained cardiologist removed a clot from his left anterior descending artery and inserted a stent to keep it open. He returned to Atlanta to recuperate. “The weeks and months that passed after the episode felt like

In six months, Jain was back at work—but he had changed. The experience opened his eyes to the insidiousness of chronic stress. “It may not manifest until much later and in different ways,” he says. “But that doesn’t mean the wear and tear

Jain himself began a strict exercise regimen and enrolled in mindfulness and meditation programs. “The world has suddenly slowed down around me, and I feel much more able to handle situations that in the past would have been disruptive,” he says. “I have a better appreciation of life and its vulnerabilities but also its gifts.”

Fill the Tank

Stress is cumulative, so it must be managed early and continually, says Sheryl Heron, who is a physician at Grady Hospital, a professor and vice chair of Emory’s Department of Emergency Medicine, and chair of the school’s wellness and well-being committee.

Factors include sleep deprivation, exposure to infectious disease, and no time for self-care.

“In the emergency department,” she says, “we drink pain and suffering every day.”

After all, patients don’t make appointments to come to the emergency department. “They don’t want to be there. They’re there due to violence, car crashes, horrible injuries,” Heron says. “What happens to doctors in our attempts to cope, keep it moving, jump on the train?”

She remembers a family she encountered early in her career—three children and an adult with multiple gunshot wounds from family violence. “One had been shot in the temple and was blinded, another in the neck and was paralyzed, another in the arm with an open fracture,” she says. “Two of the children reminded me of my nieces. I had a visceral reaction that upended me.” Fortunately, it was during a change of shift and there were other physicians there to take over. She went home, distraught, and later talked to a colleague who encouraged her to write about the experience as catharsis, which she did.

“I suspect everyone was impacted, not just me,” she says. “Now at

To cope with stressors like these, you have to “fill the tank,” says Heron. “In my younger days, I didn’t take a break to eat,” she says. “Now I do. We have to create a culture where we believe going to eat when one is hungry is normal. We become so acculturated over time, we strip ourselves of essential human needs that make us want to return to work with joy and empathy.”

Emergency medicine is simultaneously the specialty with the highest rates of burnout and the top-rated for physicians who say they love their job, which is “a bit of an enigma,” admits Heron.

Personally, she makes it a priority to go on vacations, carve out family time, exercise and eat properly, go to bed at 10, wake up early, practice meditation, and read devotionals. “I also step outside the grind and explore, reinvent myself, tap into things that intrigue me,” she says. “This is what I need to do for me and what I need to model for my residents, students, and faculty colleagues. Your life and career should go forth in tandem.”

Boost Empathy

When psychologist Nadine Kaslow hears of a mass casualty event near downtown Atlanta—the Centennial Olympic Park bombing, a multiple shooting, a plane crash—she will often head to Grady Hospital, no matter the hour. “It’s not that they need me to take care of patients, but I know the doctors and nurses need support,” Kaslow says. “So I let them tell me about what they’ve seen.”

As

“Whenever there’s something really bad, people know to call Nadine,” says Shayne. He recalls an episode earlier this year when a nurse in Grady’s burn unit died of a heart attack on the job: “Right then, Nadine came down to debrief everyone—to help them process what had happened.”

“It’s talking about what happened, but it’s also talking about the person’s experience of what happened,” says Kaslow, who over the years has recruited other colleagues to share the load, assembling an informal debriefing team.

While the team doesn’t have an official title or role, it’s clear that there exists a significant unmet need for what they do. “Every time I give a talk on this, people follow me out of the room to tell me about something they haven’t dealt with,” she says. “Every single time.”

Out of 100,000 consults by Spiritual Health at Emory Healthcare this past year, more than half have been for professional and support

“A major cause of physician stress and burnout is

While well-intentioned, this approach can overwhelm the physician with collateral emotions and lessen the trust of the patient, who senses the doctor’s guard is up. “Staying engaged with one’s story and emotions, our inner conversation, allows the clinician to model self-compassion, which is vital to a healing collaboration and builds instant rapport,” says Grant, who gives his own staff the same advice. “By practicing with our personhood intact, we are saving time and saving ourselves.”

Champion Wellness

During medical training in Philadelphia, Wendy Baer remembers her own attending encouraging her to take a break from studying for her boards to go to an art museum. He told her, “You’ll be a better doctor if you have something interesting to talk with your patients about.”

Baer sees both patients and staff in her role as

“The ‘should’ issue comes up a lot—‘I should be handling this better, I should be stronger, I shouldn’t cry or be upset.’ They have to understand they are going to experience a broad range of emotions, just like other patients do,” she says.

Physicians are quick to tell patients to eat better, exercise, quit smoking, and find healthy ways to relax. But the very practitioners that should embrace and embody healthy living and self-care have too often chosen for themselves long hours, late nights, perfectionism, and pushing past emotions.

Add to that the fact that physicians carry an average load of 2,300 patients annually. “Doctors who are super busy with their clinical practices have an awfully hard time balancing their own healthy lifestyle choices,” Baer says. “If you’re going to avoid burnout, you have to pay attention to this.

“We all need to be wellness champions in our own workplace: hold medical classes outside sitting on that beautiful lawn, spend time in nature or doing something creative,” she adds. “Apply that ‘can do’ fighting spirit and desire to heal

But individual resilience and healthy habits can only go so far.

But individual resilience and healthy habits can only go so far.

To start the dialogue, she and colleague Julie Jackson-Murphy started a newsletter for Emory’s Division of Hospital Medicine called “Not Enough Said: Candid Conversations about Life and Medicine.” “I’d love to see our community’s commitment to clinician well-being intensify, expand, and be encoded into our professional structures,” Von says. “That’s when you start to come up with some real solutions.”

Strengthen Compassion

Despite the emergence of ethics training as a core component, doctors and researchers say medical school’s so-called “hidden curriculum”—the socialization process by which norms and values are transmitted to future physicians—instructs students to be detached, objective, and self-interested.

One way to instill compassion during medical school is to teach it. While conventional wisdom might view compassion as an inborn trait, research has proven the opposite—much like other skills, compassion can be strengthened through instruction.What’s more, it can be strengthened in both fledgling and veteran doctors.

William Branch Jr., professor of medicine at Emory, led an effort in 2009 to assess a faculty development program designed to encourage humanism—seeing the value and goodness in others and acknowledging common needs and concerns. Over 18 months, groups of physician-teachers met biweekly to discuss and write about things like listening, building relationships, and adopting caring attitudes toward patients.

At the study’s end, the physician-teachers who participated were evaluated against a control group, and the former outperformed the latter across the board. “I was very surprised by the results,” Branch said at the time. “These skills can help physicians grow, not just in terms of knowing more but in becoming

Another Emory-led study suggests that learning compassion is not only possible, it can be a powerful antidote to stress and burnout. “We saw that well-being was a real problem for medical students and residents, and we concluded that it must be the process of providing compassionate care that leads to burnout,” says Jennifer Mascaro, assistant professor of family and preventive medicine at Emory, who led the study. In fact, it appears to be just the opposite.

She looked to

She looked to

Mascaro and colleagues randomly assigned volunteer second-year medical students to either 10 weeks of CBCT or to a

Restore Joy

The annual Blue Ridge Academic Health Group report, which this year focuses on health professionals’ well-being, states: “We pay a staggering cost in lost productivity, risks to mental and physical health, eroding quality and safety, diminished patient satisfaction, staff turnover, and lost dollars. At the extreme [is the] personal toll of depression and suicide. ... When joy is lacking and burnout is present, the stakes are high.”

When a group of Woodruff Health Sciences Center leaders studied clinician and staff burnout this past year, the takeaway was that

Everything from night shifts to break schedules, computer time to patient load, office procedures to information technology must be reexamined with an eye toward protecting physicians’ time, health, and well-being. “There is no amount of yoga that can help at night when you are 50 charts behind,” says group member and Emory emergency medicine physician Doug Ander. His department has instituted the use of scribes to gather and document patient information, which has helped physicians return more of their time to direct patient care and mentoring.

“Health care has traditionally emphasized the triple aim of patient satisfaction, quality, and cost-effective care,” the group concluded. “We need to add clinician satisfaction to those priorities.”

Doctors as 'Second Victims'

On a recent evening at the Sibley Heart Center, Kurt Heiss, professor of surgery and pediatrics at Emory School of Medicine and a pediatric surgeon at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, asked a roomful of cardiologists to consider for just a moment the Summer Olympic Games in Beijing.

“Do you remember what happened?” he said. “The U.S. men’s 4x100 relay team had always won gold. But in 2008 in Beijing, they dropped the baton in the qualifying round. And 30 minutes later, the women did the same thing. They didn’t even get to compete.”

On the wall was a slide with images of the catastrophe as it unfolded: outstretched hands, anguished expressions, a baton just out of reach.

“So what does this have to do with any of us?” he said. “Well, like you, these people trained their whole lives for this. They’re spectacular at what they do. Yet they made a mistake—and they don’t get that back.”

Heiss was using the analogy to kick off a presentation he has made dozens of times to doctors across the spectrum of specialties. His aim: to foster openness and honesty around medical errors and to advocate for the compassionate support of “second victims”—physicians who, having made a mistake, struggle to cope with the outcome.

If patients are the first victims of medical mistakes, then providers are the second, argues Albert Wu, professor of health policy at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who coined the term in 2000.

Yet, historically, institutions have done little to support these physicians. Anxious, depressed, and demoralized, they often suffer alone, tormented by guilt for months or even years. “It’s not only the emotional anguish,” says Heiss, who has researched the topic extensively. Plagued by repetitive replays of the event, second victims begin to think differently—they lose confidence in their skills, second-guess their decisions. In some cases, second victims switch jobs or

Heiss speaks from experience. A few years ago, he led a team tasked with operating on a boy who had been badly injured in an accident. The procedure was difficult, a member of the team made a mistake, and the patient died. With that began what he describes as “the

As he endured that ordeal, he turned to books on bouncing back from difficult experiences and discovered that resilience is not a trait but rather a set of thoughts and behaviors that anyone can learn and develop. These include attracting and giving social support, imitating resilient role models, focusing on mission and purpose, and holding to the belief that “adverse events are neither permanent nor pervasive.”

Heiss also took stock of the “culture of blame” that predominates in many medical environments, which singles out for reproach the individual who makes a mistake while ignoring systemic issues that can lead to unsafe behaviors. By comparison, a “just culture” supports learning over punishment and putting into place safeguards that can prevent errors.

Emory and Children’s have instituted a three-tiered response to

Providers can learn the skills to reach out to a colleague in need. “Our focus should be them and their feelings, to remind them of all the good things they’ve done in caring for their patients.” That said, he adds, everyone mourns differently.

If a person doesn’t want to talk,“we have to honor that. The victory for us is in the invitation.”—Patrick Adams