The Game of Life

By Rhonda Mullen

Illustration by Laura Coyle

|

Life is a fatal condition. Make the best of it. Thus ends a new book that presents a revolutionary approach to health.

In Predictive health: How we can reinvent medicine to extend our best years, Emory physicians Kenneth Brigham and Michael M.E. Johns argue for an essential shift in how we approach health care. The predictive health approach focuses on prediction instead of diagnosis and health rather than disease.

Predictive health, as the authors explain, involves defining what health is and detecting and correcting the earliest unhealthy tendencies long before there is any evidence of disease. It differs from personalized medicine, which is trying to find a drug to fix a problem. Instead it tries to get a step ahead.

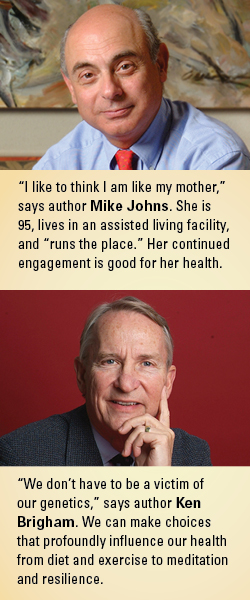

"The thinking is a matter of switching your brain a little bit," says Johns. "It doesn't mean that we won't take care of disease when it comes along. But it requires a different way of thinking."

This different way of thinking could not only extend life (and quality of life) but also save money. Much of the current health care debate in the United States focuses on who should receive coverage, how much it will cost, and who will pay for it. But too few policymakers or medical professionals have recognized the fundamental flaw in this thinking, according to the authors. They argue that disease and its symptoms are late, sometimes irreversible, and the consequence of long malfunctioning processes. Almost $175 million—or one-third of the national Medicare budget—is spent in the final year of a patient's life, and one-third of that total is spent in the patient's last month of life, often on futile and expensive treatments in an intensive care unit.

By intervening early, we could change that scenario, say Brigham and Johns. We could prevent or forestall chronic diseases such as hypertension, cancer, diabetes, and heart disease. And when people stay well longer, they will need less expensive health care.

The system will change because it must. We will not tolerate forever a health-care system that costs too much and delivers too little. Quality and access are just part of the problem. Continually escalating cost, unchecked, will drive the current system out of business.

The system will also change because it can. We live in a vortex of discovery and invention that is spinning out at a dizzying pace new tools for measuring health. We already have much of the technology for predicting an individual person's health and measuring the consequences of healthy (or unhealthy) living.

|

|

Writing your own prescription

While patients can't change their biology, they can find comfort in knowing that environment and behavior can have major influences on health. That diet and exercise have strong effects on how our body plays its genomic cards was not much of a surprise to those of us who spend our waking moments thinking about human biology. What did, and still does, surprise us (although it probably shouldn't) is that emotions also affect how genes behave. So what you eat, what you do, and what you feel all matter… Laugh and your genes laugh with you.

The Emory/Georgia Tech Center for Discovery and Well Being, which Brigham founded, seeks to empower participants to take charge of their health. Here, participants undergo a battery of biologic tests (including measures of body fat, bone density, circulatory function, inflammatory status, physical fitness, and brain function). Four processes that play a fundamental role in most diseases—inflammation, immunity, oxidative stress, and regenerative capacity—are charted, and samples of blood are drawn and stored in a biobank. Participants take surveys on lifestyle choices, the environment in which they live and work, and their behavior. They receive a health assessment report that compiles the findings, and they then work with a predictive health partner to develop a personal health action plan.

In general, after six months to a year in the program, participants have lost weight, their blood pressure and blood sugar levels have dropped, and blood lipids and biomarkers of inflammation have improved. Well-being also improves with the perceived decrease in stress, improved quality of life, and less depression.

After his own evaluation, Brigham began to exercise more and pay closer attention to his diet. With a few simple modifications, his risk for heart disease on the standard Framingham risk measurement plunged by 40%. Johns made similar adjustments based on his assessment. He found a personal trainer who is an ex-marine, and he purposely eats "more seafood than moo food," he says. "I feel no obligation to eat everything on my plate like I did when I was a kid growing up in a less than affluent house in Michigan. Now it's about portion control."

But say a person gets the tests and the measurements, understands the consequences of his or her behavior, and follows the predictive health prescription, is success guaranteed? As a society, we might have to do more, write the authors.

To succeed, predictive health must change the game, and not just by replacing the obsession with fighting disease with an emphasis on defining and preserving health. Predictive Health aims to disrupt everything you and the medical community know about health care… A primary need is for a new mindset; measurements are not made to establish a diagnosis but to define the status of a person's health. Predictions based on data are not of risk for a heart attack or Alzheimer's disease, but the odds of staying healthy. And that new mindset requires a new vocabulary. Words and how we use them matter. People are people, not patients. Healthy people encountering the care system should neither perceive themselves as patients nor be perceived that way by care providers. They must be understood as real human beings, with all of the marvelous potential that that implies, and our job as health-care professionals is to help them see that potential and go about realizing it.

|

|

Live and let die

Now back to that book ending, the inevitability that life is a fatal condition.

In a survey of what is important to people who are dying, more than 70% ranked the same 10 things, all of which are fairly easy to accomplish: be kept clean, name a decision maker, have a nurse with whom one feels comfortable, know what to expect about one's physical condition, trust one's physician, have one's financial affairs in order, be free of pain, maintain a sense of humor.

While the growing specialty of palliative care and the hospice movement are making strides toward granting those requests, dying for many Americans does not happen in the peaceful and caring confines of a hospice or at home surrounded by loved ones. More than 20% of dying Americans spend their last days in an expensive, high-tech hospital intensive care unit.

The predictive health approach begins in a sense by looking at the end, by acknowledging that everyone will die, by knowing that our lifetimes are brief, by challenging us to make healthy choices and live well. How would we live if we experienced our mortality, realized how short the time is and how sure the final outcome, before being faced with an incapacitating illness? It seems likely that such a realization, internalized, would trigger some rearranging of priorities for most of us. And the reality of an inescapable end to what will be a too-brief life no matter when it ends could be liberating. EH

|

Meet Hilda Echt, an affluent 100-year-old Atlantan, who was interviewed for this excerpt from Predictive Health:. "What do you think is the thing old people need the most?" she asked her doctor visitor. "Medical care" was his stock answer. "Hogwash," she replied. "If you get to be as old as I am, you get medical care. Otherwise you'd have died off a long time ago. It's transportation. Getting places just to do the essentials is a problem, much less going out and among people. I drove until I was past ninety. Without that car, I'm grounded like a naughty teenager." When the conversation turned to death and dying, Ms. Echt said, "I want to drop dead… but not yet." She died two years later. Maybe she was ready by then. Socially engaged people do live longer. Information relevant to this point comes from studies of men in Sweden. Socially engaged Swedish men lived significantly longer than their less-engaged peers. That was true even when all other health-related information was taken into account. It was also true whether the men were born in 1913 or 1923. There is something vital about mingling with our kind. |

To see a video about Predictive Health, visit bit.ly/ourbestyears. To hear the authors discuss their book, visit bit.ly/phbookreport. |