The Earlier the Better

By Sylvia Wrobel, Deriso family photos by Jack Kearse

When five-year-old Walt Deriso finally made it to the top of the waiting list at the Marcus Autism Center, he spoke only three words. He wasn’t toilet trained. Distraught, often enraged, he threw tantrums. He ran away.

"Anna and I had loved him since he came into our family at five days of age," says his adoptive father, Walter Deriso III, "but we had no relationship with him."

|

When the therapists and staff at Marcus first encountered the young boy, they encouraged him to put the things that interested or scared him on paper. Although seemingly disengaged, he drew happy scenes from a recent family vacation at the beach, perfectly spelled out words from a favorite video, and portrayed faces that showed different emotions. The therapists used the drawings as a springboard to work on Walt’s lack of speech and behavioral issues and to help his parents build a relationship based on what their son was curious about.

"Our challenge," says his father, "the challenge of all parents of children with autism, was to figure out how to connect with him, to make him care enough to come into our world so we could help him use his gifts."

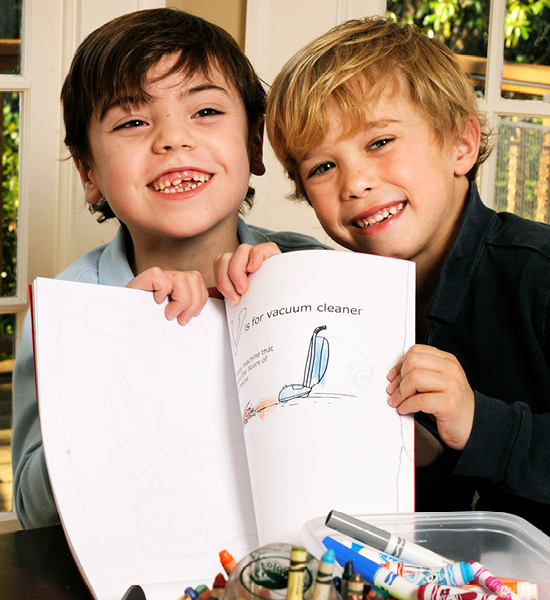

When intensive applied behavioral therapy did open that world to Walt, it turned out that he had a lot of emotional and intellectual gifts on which to draw. Four years later, the energetic nine-year-old is quick to grin, chatter, tell his parents he loves them, and enthusiastically hug visitors. In fact, the lessons in expressing affection have worked a little too well, and his parents are working to fine-tune the behavior. "He has to learn not to embrace every pizza delivery man!" says his mom, Anna Deriso.

The world fascinates Walt, even if in a very different way from his younger brother Henry. A typical five-year-old, Henry shares his parents’ love of sports, closely following the Atlanta Falcons and all the teams at Vanderbilt, the family’s alma mater. Little Walt’s current passion is vacuum cleaners, on which he is an expert. Last year, to his parent’s complete bewilderment, UPS delivered a new vacuum cleaner to their doorstep. Their oldest son, who only three short years earlier was unable to talk, much less read, explained how he had used his mom’s credit card to order the vacuum cleaner on amazon.com. He had selected the one with the highest rating and asked for one-day delivery.

Walt attends school at the Marcus center five days a week, six hours a day, in addition to private speech therapy, occupational therapy, and special swimming exercises—"more hours than most adults work per week," says his dad. And if Walt works hard, so do his parents. Walt Deriso III is senior vice president at Atlanta Capital Bank, where his father and Walt’s granddad, Walter Deriso Jr., an Emory Trustee, is chairman. Anna Deriso is a nurse practitioner. Having a child with autism is the third job in the family—requiring hours of therapy and mountains of paperwork. But since Georgia is one of the states that covers little in the way of autism care, neither of Walt’s parents has the luxury of not working.

The Derisos also feel a commitment to help others as they have been helped. Every week, they talk by phone or in person with parents who have a child who may have autism. They are active in the national nonprofit Autism Speaks, and they raise money for scholarships at the Marcus Center, where Walt III serves on the board and where tuition for one-on-one treatment costs more than a year at Harvard.

It’s hard, admits Deriso, but "it’s worth every minute, seeing the progress that Walt is making."

|

|

Big changes on a short timeline

Entrepreneur and philanthropist Bernie Marcus created the Marcus Autism Center more than two decades ago after watching an employee struggle to find resources for her newly diagnosed son. Then and there, Marcus decided to hire a developmental pediatrician to help the employee—and allow her to stay in Georgia instead of moving to another state that has insurance coverage for the disorder. Working to mitigate autism and understand how to better diagnose, treat, and prevent it is a slow, expensive process, but as Marcus has said for years, it’s a financial as well as moral obligation. It now costs more than $3.2 million to care for a person with autism over a lifetime.

Ami Klin never planned to leave Yale, where he headed one of the country’s most prestigious autism research programs. When Marcus came calling, even talking to him and the prominent members on a search committee felt, he says, like cheating on his wife. "Then pick up the phone and tell her you’re coming," Marcus told him.

At Yale, Klin and his team had reached a breakthrough in eye-tracking research that detected signs of autism as early as infancy, which could lead to earlier interventions when the condition is most malleable. They were ready to move the science into broader clinical practice, demonstrating its power and expanding its impact, and, as many in the field believed, changing the autism landscape.

The team saw 300 children a year at Yale. By comparison, clinicians at Marcus, the biggest program in the world by far, see more than 5,500 children a year. The center is involved with thousands more statewide through strong community partnerships. Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta (CHOA), the home organization of Marcus since 2008, embraces research-based care as part of its mission. The Emory School of Medicine, its chief academic partner, has strengths in the genetics and neuroscience of autism, and Emory’s pediatrics department has a newly created division of autism and related disabilities.

The Georgia Research Alliance (GRA) and state officials called Klin in New Haven to personally express their commitment in making Georgia a leader in autism research. Marcus and Russ Hardin, president of the Woodruff family of foundations, suggested that Klin recruit a dream team and build a new research infrastructure. "It was an unprecedented opportunity for myself and my colleagues," recalls the researcher, "but more important, for our true constituents, the children and families impacted by autism."

Klin arrived in Atlanta to assemble his team early in 2011. Many of his colleagues at Yale, 22 who are leaders in their field, followed. That raised the number of clinicians and researchers at Marcus to more than 180.

"Ami Klin has an incredible exuberance about science, spurred by his conviction that we can improve outcomes," says Barbara Stoll—George W. Brumley Jr. Professor and Chair of Pediatrics at Emory and medical director of CHOA at Egleston. "Clinically, research-wise, and with one of the best training programs anywhere, the Marcus Center is humming. If I were 25 again, that is where I would want to go work."

Since Klin’s arrival, the NIH has created an Autism Research Center of Excellence (ACE)—one of only three in the nation—with an $8.3 million award shared by the Marcus Autism Center at Children’s, Emory’s pediatrics department, and Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory. Klin added principal investigator and ACE director to his titles as director of the Marcus Center, GRA Eminent Scholar, and Emory professor of pediatrics. He and a coalition of autism resources in Georgia had done in months what had taken other centers a decade. Governor Nathan Deal announced the "transformational grant" in the Capitol. Efforts for widespread early detection and intervention were poised to take off.

|

|

Tracking the social brain

Typically developing infants prefer to look at human faces, especially the eyes, and at what scientists refer to as "biological motion." True across the species, this behavior has evolutionary advantages, helping parents bond with helpless offspring and making youngsters aware of predators. The most common signs of autism—the ones that parents usually recognize first—are what attracts their children’s attention (preferring objects to playmates) and how it affects their social interactions (seeming uninterested in others’ feelings).

These differences appear to be hardwired. Since developing brains can be changed with early enough intervention, early detection becomes "an ethical imperative," says Klin—especially now that a diagnostic tool exists.

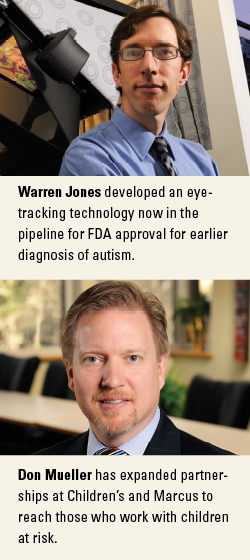

The eye-tracking technology in use at the Marcus Center was developed by Warren Jones, then a student at Yale and now an Emory faculty member and research director at Marcus. A dual art and engineering major with a part-time job teaching art to autistic children, Jones became fascinated with how the drawings of otherwise uncommunicative children left a map of how they see the world (as young Walt Deriso’s did). Jones built a rudimentary device tracking how the children’s eyes moved, then turned to a leading autism expert for advice on how to improve it. He won one of the American Psychology Foundation’s highest honors for the instrument and subsequent work.

Using the noninvasive technology, a child (or infant) watches a video in which mothers interact with babies or toddlers play together. Cameras track microscopic movements of the pupil, hundreds per second, recording what draws the child’s attention. Typical two-year-olds, for example, watch social interactions intently, their eyes moving back and forth as if following a social tennis match. Those with autism focus on a different aspect of the video, such as a door opening and closing.

Taking the science to patients

The best clinical experts can diagnose autism at 18 months of age. Five years ago, three-year-olds were the youngest children whom researchers ever had a chance to see. Now, thanks to eye-tracking technology, they can follow children from birth and watch the condition unfold, says Klin.

Celine Saulnier, Emory researcher and clinical director for research at Marcus, says that the studies supported by ACE funding use the eye-tracking technology to identify children in their very first year and then measure the effects of treatment by the time they turn 2. A study by scientists at Yerkes uses eye-tracking measurements to quantify social behavior in infant rhesus monkeys in the first months of life. These studies also include noninvasive brain studies that focus on brain changes resulting from early social experiences.

In a study of social visual engagement in infants, as measured by how they look at people, Jones and Klin are evaluating the social development of 330 babies 13 times over the first two years of life. Clinical evaluations take place between nine and 36 months. Two-thirds of the participants have autistic siblings, making the risk of having autism in these babies shoot to one in five compared with one in 88 in the general population, thereby raising the likelihood of having infants with autism in the study.

A study of social vocal engagement, headed by Emory researcher Gordon Ramsay, director of the Spoken Communication Laboratory at Marcus, builds on studies that begin even earlier. Ramsay records the responses of babies to their mother’s voices while still in utero. With funding from ACE, recordings are made every month from birth to age 2 to test whether social engagement predicts speech and language outcomes.

In all of these studies, children identified as at risk receive additional monitoring and attention, and those who are found to be at risk for autism are then enrolled in a treatment study beginning at the age of 12 months, the earliest of its kind in the country. "We’d rather give a child without autism too much attention than risk not giving a child with autism enough," says Saulnier.

The treatment study focuses on the development of better interventions for younger children. Using a protocol developed by Amy Wetherby, a professor of communication disorders and speech pathology at Florida State, Wetherby and Nathan Call, Emory pediatrician and director of behavioral treatment clinics at Marcus, are testing the efficacy of community interventions in which providers go into the home and train parents.

The researchers hope to demonstrate in large populations what they already have found in small ones. Seeing thousands of children means that they will be able to work with autism’s "orphan" groups, whose smaller numbers of autism diagnosis often exclude them from research. Those groups include girls, African Americans, and other minorities.

The scientists also are embarking on an FDA clinical trial using the eye-screening technology to identify children with autism. They hope that the technology can become part of healthy baby screenings, giving community doctors a quick and easy tool to use to identify infants at risk. And that could help families get help that can change the course of autism earlier, which could make all the difference.

As Walt Deriso says, "They all feel that dual sense of burden and opportunity, and they all work together to change the lives of children like Walt and the future of autism. There is so much riding on this. The magnitude of the possible change cannot be overstated." EH

Autism resources To see a video of Walt Deriso discussing his family’s experiences with autism, visit bit.ly/autismparent. The Emory Autism Center in psychiatry and behavioral sciences offers the largest staff of specialized autism providers in Georgia, offering diagnosis, family support, and treatment and serving as a vital source of training. psychiatry.emory.edu/PROGRAMS/autism, 404-727-8350. The Marcus Autism Center, an affiliate of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, diagnoses and treats children with a wide range of neurologic problems, including autism spectrum disorders. Staff work with parents to find ways to help children cope with their disability, including carefully managed therapy to teach children to circumvent barriers posed by the disability. Marcus.org, 404-785-9400. To contribute to autism research and programs at Emory, contact Margaret Lesesne, director of development for clinical programs, at Margaret.lesesne@emory.edu, 404-778-4632. |