Amazing Deliveries

By Marlene Goldman

Edita Tracey plays with her daughter Arabella. Jack Kearse

|

Amazing Deliveries: |

Arabella: A powerful presence

Edita Tracey, an accountant unwinding after a high-stress tax season, was eight months pregnant and at a Buckhead hair salon this past April when the back pains started. Then came dizziness and chest pain.

"I couldn't drive my car, and my husband was in Chicago on a business trip. I waited 30 minutes," says Tracey, whose 2-year-old daughter, Savannah, was at her grandmother's house in Buckhead. "But the pain was like none I'd ever had, and that's why I called 911." She doesn't remember what happened after the EMTs arrived.

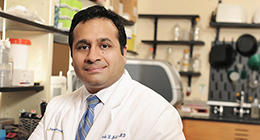

Omar Lattouf, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Emory Midtown Hospital, and his wife, Emory pharmacist Lina Lattouf, had been invited to dinner that evening by a former patient—a dignitary from Jordan he had operated on six months earlier. They were about to be seated at La Grotta in Buckhead when Northside Hospital ER called for an urgent consult.

Viewing Edita Tracey's CT angiogram on his iPhone5, Lattouf was astounded.

In his 29 years of practice, he had never seen anything like it—a massive foot-long tear in her enlarged aorta and blood pooling around her heart. "Then they told me that she was also having contractions," Lattouf says.

He called the OR at Emory University Hospital Midtown, high-risk obstetricians, an anesthesiologist, the intensive care unit, his surgical team, perfusionists, and nurses. Within five minutes everyone was on the way to the hospital.

|

|

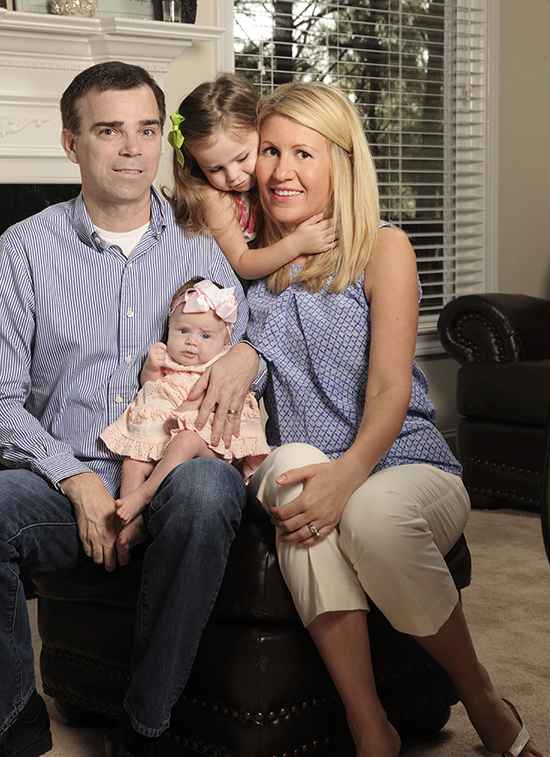

Ken and Edita Tracey with their two daughters, Savannah and Arabella, enjoying time together at home, which they no longer take for granted after a near-fatal medical crisis during her pregnancy.

|

Two surgical units—more than 20 people in all—had assembled just a half hour later and were waiting in a pair of operating rooms when Tracey was airlifted to Emory Midtown. Lattouf and her Northside physician took personal responsibility for the air ambulance in order to bypass a protocol that prohibits transporting near-term pregnant women. "The risk of her aorta blowing out was much higher than the risk of her having the baby during a ten-minute helicopter ride," Lattouf says.

The surgical team, led by Emory obstetrician John Horton, knew that the full-sleep anesthesia given to the mother would be racing toward the baby, and that they had to move quickly.

In 30 seconds they had the infant out— a healthy, screaming 6-pound, 12-ounce baby girl who, Lattouf says, filled the OR with her presence. "I made up my mind then that if this woman didn't survive, I probably was going to have to quit heart surgery because I couldn't live with myself if that baby didn't have a mother," he says.

The odds were not good. Lattouf had just told a weeping Ken Tracey, who had taken an emergency flight home from Chicago, that his wife had a 50% chance of surviving. With his wife still in surgery, he met his youngest daughter for the first time. "It was surreal," he says, "seeing my brand new baby daughter and worrying if Edita would make it or if I would be a single father of two."

|

"The risk of her aorta blowing out was much higher than the risk of her having the baby during a 10-minute helicopter ride." —Dr. Omar Lattouf |

Back in the OR, Lattouf was facing one of the most challenging surgeries of his career. "She had fluid around her heart and this huge tear and I couldn't guarantee anything. I had done more than 10,000 heart procedures but nothing like this," he says. "I was scared and knew we had to do it right the first time. It was a life-changing operation for me."

Over the next eight hours, the surgery team opened Tracey's chest and put her on a heart-lung bypass machine. "We basically had to reconstruct everything," Lattouf says, including the aortic arch and the blood vessels that went to Tracey's arms and brain.

"With every stitch, that newborn baby commanded the room and overpowered everyone there," Lattouf says. "We all knew we had to ensure that she had the future she deserved."

After the operation, Tracey suffered other complications—a seizure and high blood pressure. But she woke up the next day in the intensive care unit and was able to hold her daughter for the first time. The relief was palpable as Tracy recognized her husband and her sisters.

One of the first medical staff members she saw was anesthesiologist Sophia Fischer, who asked if Tracey remembered her from an earlier encounter. "I came to the US 15 years ago from Bosnia via Germany," Tracey says, "and I took some entry-level English classes with Dr. Fischer at Kennesaw State University."

Arabella is now three months old, smiling and making happy baby noises. Tracey occasionally stops by to visit Lattouf and is under the care of Emory Midtown's high-risk OB cardiologist, Dan Sorescu, who has since learned more about her family history. Tracey's father died young from what was suspected to be a burst aorta, probably the result of stress during the war in Bosnia, high blood pressure, and possibly Marfan syndrome, a genetic disorder that affects the body's connective tissue and can cause aortic enlargement.

Sorescu, who sees every pregnant woman with a heart condition at Emory Midtown, says Edita Tracey's and her baby's survival may be "the most dramatic case I've ever seen. Not only is the mortality rate high for such an aortic dissection, pregnancy also increases the risks since pregnant women have very soft tissues that can rupture easily."

Tracey's experience prompted her sisters to have heart checks, and a children's cardiologist has given Arabella and Savannah a clean bill of health.

The emergency delivery and surgery seem hazy now, almost like a dream to Tracey. "Sometimes we forget about how important the little things are until something major happens," she says. "I still can't lift Savannah, but I can hold the baby. I'm so fortunate to be here with them. I'm back at work, but I've learned to slow down. My advice is to follow your own instincts. If you have pain that you've never had before, call your doctor. I'm so grateful for all my doctors and the staff who cared for me."

"That's our job," Lattouf says. "That's what we do and what society expects of us. We take care of patients and give them back to their families."

Amazing Deliveries - Avery and Brantley: The dynamic duo

When she was 14, an automobile accident paralyzed Ashley Patton from the waist down. Being in a wheelchair, however, didn't stop her from leading an active, independent life.

When Ashley became pregnant with twins at age 21, she and her husband, Alex, a former Marine who is also a twin, were excited. "We called them Baby A and Baby B," she says.

But soon Ashley's morning sickness became so bad that she was hospitalized and needed medication and IV fluids. Then, six months into her pregnancy, she had an episode where she couldn't catch her breath. "My stats were going crazy, my blood pressure was dropping, and my oxygen was low," she says.

|

|

Alex and Ashley Patton play with twins Avery and Brantley at their home near Lake Lucerne. The boys love trucks, balls, and dinosaurs.

|

Referred to specialists at Emory Midtown, she was diagnosed with a three-inch blood clot that had traveled from her legs into her heart. Dangling in both the right and left atria, it was moving with every heartbeat. If it broke free, it could cause a stroke or even death.

After a consult with critical care medicine, pulmonary medicine, high-risk obstetrics, cardiac anesthesia, and cardiology specialists, the group decided to proceed with a Caesarean section and open heart surgery. The staff cleared two operating rooms, gathered three surgical teams and two teams of adult and neonatal intensivists.

"We had one mom, three lives, and three operations," cardiothoracic surgeon Omar Lattouf says.

"I went to pre-op and there were 20 or 30 doctors figuring out what to do," recalls Patton. "They told me I needed open heart surgery, but they wanted to do a C-section first to deliver the babies early because the twins would have a better chance than if they had to go under anesthesia. It was a hard choice but I trusted the doctors."

|

"The clot presented a potentially fatal medical problem. While still within mom, the preterm but viable twins couldn't survive without her." —Dr. John Horton |

As a part of the Obstetrics Rapid Response Team at Emory Midtown, obstetrician John Horton is routinely involved in urgent and emergency Caesarean sections. But this case was more complex, he says, and needed multiple medical teams working together to save mother and babies.

"The clot presented a potentially fatal medical problem. While still within mom, the preterm but viable twins couldn't survive without her," he says. "Ashley needed a pump to circulate her blood during heart surgery, but that might not have been enough for the growing twins. Because of the heavy sedation required for heart surgery, our OB team had to be very efficient, very quick to get the babies out while still keeping the mom safe."

In the first OR, the obstetricians quickly delivered the twins. Neonatologist Ann Critz was waiting to take over their care. Avery weighed in at 1 pound, 12 ounces, and Brantley, 2 pounds, 3 ounces. They would stay in neonatal intensive care for several months.

In the second OR, Ashley was put on a heart-lung machine. The surgical team opened her chest and, in what Lattouf says was one of the most complicated surgeries in his almost three decades of practice, he removed the clot from both sides of the heart.

"It was like someone shoots a bullet and you have to go in and grab that bullet before it hits the target," Lattouf says. In a third surgery, the surgeons placed a stent.

Lattouf, who specializes in thrombosis, says there are many causes of clot formation, including pressure from a pregnancy on the inferior vena cava (the large vein that carries deoxygenated blood from the lower body into the right atrium of the heart).

Being sedentary can also be a factor.

"In fact, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolisms are among the most frequent causes of death in pregnant women," he says.

Ashley Patton was able to hold Brantley two days after her surgery, and Avery two weeks later. Another surgery followed to drain fluid from her heart, and more recently, she was put back on blood thinners, this time probably for life, after another clot was discovered in her lungs.

Fraternal twins Avery (Baby A) and Brantley (Baby B) are now nearly 3, and the Pattons' Buford home is filled with trucks, balls, and other toys. Avery is laid back and happy to look at books and entertain himself, while Brantley, their "wild child," is curious, constantly on the move, and into everything.

Amazing Deliveries - Tyler: Tiny but determined

Lillian Calloway was just 24 weeks pregnant, barely to the point of her baby being able to live outside the womb, when her contractions began on June 13.

She was partially dilated by the time she got to the emergency department at Emory Midtown.

The maternal fetal medicine team prolonged her pregnancy with medication for a few days, but when Calloway developed a fever and the baby's heart rate increased, obstetrician Cherie Hill knew that mother and baby were in jeopardy.

|

|

Obstetrician Cherie Hill, an assistant professor in the medical school, often has to balance the health of a mother with the early delivery of a child. Premature infants delivered at Emory Midtown are cared for in the NICU.

|

"She had developed chorioamnionitis, an infection in the amniotic fluid that surrounds the baby," Hill says, noting that the risk of infection increases when the cervix dilates early, and sometimes after the water breaks, because of vaginal exposure to bacteria. "We couldn't allow her to stay pregnant any longer."

The baby delivered quickly, weighing in at 15.8 ounces. He was intubated to help him breathe, and whisked to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) by the neonatal resuscitation team, which attends all high-risk deliveries at Emory Midtown. "The biggest concern about babies born so early is that their lungs aren't developed. They also don't feed well, and there can be bleeding into the brain," Hill says.

The obstetrics team also was concerned about Calloway, who had begun bleeding heavily but had not discharged the placenta—not uncommon in such early term deliveries. The team moved to the operating room to remove her placenta and scrape the uterine lining, using ultrasound guidance.

Calloway was at particularly high risk because of two prior Caesarean sections. "The placenta sometimes attaches to the scar on the uterus left by an earlier C-section and can cause additional bleeding so we needed ultrasound to make sure we got it all," Hill says.

With the bleeding under control, Calloway recovered quickly and was discharged two days later from the hospital. The first time Calloway saw Tyler, he was a day old and so tiny that he could fit into one hand.

It wasn't until about a month later that she actually got to hold him.

"When I first saw him in the nursery, I didn't think he was going to make it," she says. "He was so small and weighed less than a pound." But by late July, he was breathing on his own and gaining weight.

Hill has delivered more than 500 babies during the past five years, but says it's never easy tending to extremely sick patients who deliver so early in their pregnancies.

"It's all a collaborative effort between the physicians, the nurses, the anesthesiologists, the NICU, and the blood bank," she says. "The outcomes are better because we have a process in place and immediate access to a specially equipped cart with supplies to handle bleeding emergencies."

"Our team approach is innovative," she adds, "but I hope someday it will become the standard of care everywhere."

Tyler is now breathing on his own but is expected to remain in the NICU for another few months before going home to join siblings Toure, 2, and Jessoure, 1, who has learned to say the word "baby" since visiting her new brother.

Emory University Hospital Midtown's neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), which opened in 1981, was the first in the Southeast. Its level III unit has 36 beds and the staff cares for an average of 600 premature or critically ill babies each year. |