Tackling stroke

By Sylvia Wrobel, Photography Jack Kearse

|

In 2001, during "the best season a defensive lineman could ask for," David Jacobs began suffering severe headaches after a particularly hard-hitting University of Georgia (UGA) game. He felt dehydrated, despite intravenous fluids. He was lethargic and out of it, says girlfriend Desiree, now his wife and mother of his two young sons. But he wanted to tough it out.

Four days later, after an intense practice, Jacobs's right arm suddenly went numb. His eyes turned bloodshot, and the headache worsened. He passed out and had to be revived. He remembers teammates calling, "David, David, what's wrong?" He remembers thinking the ambulance driver would get in trouble for going so fast.

That evening in Saint Mary's Hospital in Athens, he felt spacey, but the next day things went from bad to worse. He couldn't move or talk. A CT scan showed damage to the lining of the vertebral artery, probably from a blow to his head during practice. A clot had broken free and lodged in his brain. When doctors said they were transferring him to Emory University Hospital (EUH), his first thought was, "in rush hour traffic?"

Today, having become an unintentional expert on stroke care, Jacobs knows that hospitals are connected by protocols and helicopters and that he probably owes his life not only to Emory's stroke program but also to doctors at Saint Mary's. "As a hospital that treats lots of strokes, they could have been all ego," Jacobs says, "but instead they looked at me and said we need to get this kid to the specialists."

Jacobs woke up in Emory's ICU, surrounded by white coats, family, and coaches. If clot-busting medicine failed to work, surgery was an option.

Stroke primer |

That proved unnecessary, but Jacobs's battle had just begun. His right side was paralyzed. He says, "The week before I was on the field like a gladiator. Now I was like a baby, having to relearn everything." How to walk, use a pencil, talk without slurring words. Football taught him to be strong, but when a physical therapist asked him to lean on his elbows, it was the hardest thing he had ever tried to do.

He spent a month in EUH, three months in therapy at the Emory Center for Rehabilitation Medicine, more months in daily rehab with a UGA athletic trainer. Jacobs returned frequently to Emory for checkups and later to visit the clinicians and therapists who had become like family.

He received motivation from not only his clinical team but also UGA Coach Mark Richt (later godfather of the Jacobses' firstborn) and his teammates who took those first steps with him around the hospital during his recovery. A year after his stroke, at the pregame entrance of the UGA/Georgia Tech game, a fully-suited Jacobs got a thunderous standing ovation when he jogged out to midfield with his teammates.

He would never play football again, but today the successful mortgage account manager often returns to UGA—and to high schools, churches, and community centers across Georgia—to talk about stroke and the importance of quick response. He volunteers at hospitals and serves on Children's Healthcare of Atlanta's board. He recently headlined a 5K race at Saint Mary's to raise awareness for the disease that threatened his life. Just by standing there, says Desiree Jacobs, her husband is proof of what good treatment and determination to do the long, hard work of rehabilitation can do.

A decade ago, when Jacobs was referred to Emory, a sea change was occurring in stroke treatment—and Emory doctors were at the forefront of the changes.

The FDA approved the clot-busting tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in 1996, following national clinical trials involving Emory doctors. One of those, neurologist Michael Frankel, has directed Emory's Vascular Neurology program for the past decade and now also directs the Marcus Stroke and Neuroscience Center at Grady Memorial Hospital, established with a multi-million dollar gift from the Marcus Foundation.

In 2002, with support from MBNA America (since acquired by Bank of America), a new Emory Stroke Center pulled down departmental walls between neurologists, neurosurgeons, radiologists, and other specialties involved in stroke diagnosis and treatment, integrating stroke care in a model of cooperation copied nationally. Founder Daniel Barrow, MBNA/Bowman Chair of Neurosurgery, remains director, with neurologist Fadi Nahab as the medical director.

As patient volume increased, so did sub-specialization. Barrow, for example, now spends most of his time on aneurysms and blood vessel malformations of the brain and spinal cord. Volume translates to experience, and experience to better outcomes. EUH has become one of the largest referral centers in the country for hemorrhagic strokes. But whatever complicated problem arrives at the door, the team has taken care of it many times over, achieving mortality ratios well below those of the region and nation despite a disproportionate share of complex cases.

Stroke patients have special monitoring and treatment needs. Many have coexisting medical conditions. Complications can involve other organs—and may require the care of cardiologists, endocrinologists, pulmonologists, or other specialists. Emory's Owen Samuels was Georgia's first neuro-intensivist, a subspecialty that coordinates neurologic and medical management of critically ill patients. He created one of the country's first neuro-critical care services at EUH, where staff now include eight fulltime neuro-intensivists and 19 neuroscience-trained nurse practitioners. Emory's 20-bed neuro-ICU opened in 2007, centralizing critical medical services and technologies for patients suffering stroke and other severe neurologic problems. As described in a front-page Wall Street Journal article, unlike traditional ICUs that work to keep visitors out of the way, the high-tech Emory neuro-ICU comes with family living quarters and a staff of clinicians who bring families into medical conversations. As a result, outcomes have improved.

In April and July, respectively, the programs at EUH and Grady became the first in North Georgia to receive Comprehensive Stroke Center certification from the Joint Commission, the accrediting body for all U.S. hospitals. This highest possible rating recognizes institutions with specialists, programs, and clinical resources to treat stroke patients of any complexity, around the clock, with accuracy and speed.

In addition, EUH Midtown, Emory Johns Creek Hospital (EJCH), and Emory Saint Joseph's Hospital (ESJH) are now Advanced Primary Stroke Centers. Emory-affiliated Southern Regional Medical Center also holds Advanced Primary Stroke certification. Each year, among EUH, EUH Midtown, Grady, EJCH, and ESJH, Emory clinicians treat roughly a quarter of the 20,000 stroke patients in Georgia. EUH and Grady are two of the nation's highest-volume hospitals for acute stroke, each admitting roughly 1,000 patients per year, the majority at Grady for ischemic stroke (which accounts for 87% of all strokes) and the majority at EUH for the rarer but potentially more devastating hemorrhagic strokes.

The unusually high number of primary certified stroke hospitals in Georgia owes much to being part of the first wave to join the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry.

Stroke symptoms |

Established in 2001 and named for the Georgia senator who died of stroke while in office, the registry tracks hospital stroke care and shares best practices. It is based on a prototype implemented at Grady by Emory medical faculty. Fadi Nahab believes that cooperation between the expanding network of "stroke-ready" hospitals and the increasingly coordinated transfer and transport system that quickly gets patients to the right level of care is "one of health care's great emerging success stories."

More than half of Emory's acute stroke patients are transferred in, most by helicopter, from other hospitals seeking specialist care for patients. The rest come through the Emory emergency department, where emergency medicine physicians work closely with colleagues in stroke. Emory and Grady stroke teams also work closely with emergency medical service personnel to help them recognize stroke symptoms and decide where patients should be taken.

To be effective and prevent damage to the brain, tPA must be given within a short window of time. Emory already has a "door-to-needle time" of within 60 minutes for the majority of ischemic stroke patients for whom tPA is appropriate. The goal now, says Nahab, is to shorten "first medical contact-to-needle" time.

The Emory team accomplishes this quick intervention through every means possible, depending on the type of stroke or risk. This includes injecting tPA in a vein in the arm or using a catheter to release it directly into the area of the brain where the stroke is occurring. More often, it involves pulling clots through a catheter. Or performing surgery or coil embolization to prevent blood leakage or bursting of aneurysms. Or using surgery to repair (or radiation to shrink) arteriovenous malformations (a tangle of faulty arteries and veins that can rupture within the brain). More than 50 ongoing research projects by Emory investigators also develop and test new treatment methods and devices, providing patients with access to clinical trials. For example, a nationwide study known as TREVO-2—headed by Emory neurologist Raul Nogueira, who directs neuroendovascular services for the Marcus Center—led to FDA approval of a new clot-removing device in 2012.

When no treatment options seem to exist, Emory doctors go looking for other answers. For example, a patient recently referred to Emory had an aneurysm so large and delicately placed that repairing it required stopping blood flow to the aneurysm—and thus to the brain—for a full 15 minutes, which ordinarily would result in a neurologic disaster. However, working with Emory cardiac surgeons, Barrow put the patient on bypass machines used in open-heart surgery, cooling her body to the point where, as sometimes happens when a child falls into an icy lake, the woman's brain slowed so much that her oxygen demands plummeted. The team made the repair, restarted circulation, and the patient—untreatable by any standard method—went home healed and with normal function.

After stroke, most patients require at least some rehabilitation, says Catherine Maloney.

She heads the Emory Center for Rehabilitation Medicine (CRM), where stroke affects the largest percentage of the 650 inpatients and 1,600 outpatients treated annually.

Rehabilitation often begins in the EUH neuro-ICU, where rehabilitation specialists evaluate swallowing and other immediate critical problems and determine ways to quickly re-engage damaged neural pathways. These patients and others referred from across the state go on to intensive inpatient and outpatient therapy in the CRM. Many participate in groundbreaking research such as that by neuroscientist and physical therapist Steve Wolf that was the first to show the benefit of constraint-induced therapy to improve post-stroke recovery.

Once patients are largely functional, CRM "post-graduate" specialty clinics fine-tune specific speech, cognitive, or mobility problems. One clinic focuses on aphasia, difficulty in reading or finding the right word. Another provides driver evaluation and training to get patients back on the road. Others focus on strength and balance problems with therapy on stairs, rails, or in the heated water of an adaptive pool. In the wheelchair clinic, therapists work with patients and vendors to customize chairs for maximum independence. Personalized therapy helps with simple but life-affirming tasks like putting on mascara or firing up the backyard grill.

Emory patient Susan McKessy "totally gets rehab." A year after retiring from the Coca-Cola Company, McKessy, then 55, inexplicably found herself lying on the floor, vomiting, with the worst headache of her life. She crawled to a phone and asked the friend for whom she was babysitting to come home. She assumed she had contracted a virus, to which she didn't want to expose the newborn.

Although McKessy drove herself home, she did accede two days later to her sister's suggestion to see a doctor. Her internist at Piedmont Hospital took one look at his patient and had McKessy taken immediately to the emergency department. "Apparently my brain and mouth were not working at the same speed," says McKessy. A CT-scan showed bleeding in her brain. McKessy arrived at Emory at 2:30 p.m. for an angiogram that within an hour had outlined a bulging aneurysm. Two hours later, she underwent what she calls "rocket science surgery," in which interventional neuroradiologist Jacques Dion snaked platinum wires through blood vessels to her brain to create delicate coils that sealed off the aneurysm.

Placed in a coma to give her agitated brain time to rest, McKessy remembers nothing of the surgery nor of the following days in the neuro-ICU. After weeks of rehabilitation, when she "met" Owen Samuels, who had participated in her immediate care, she didn't remember him. He almost didn't recognize her either, so completely had she recovered.

Still, it wasn't easy. Now a volunteer at the CRM, McKessy often shares her own story with patients—how a physical therapist had told her, yes, she understood that McKessy didn't want to do therapy because she was tired, sleepy, discouraged, etc., but none of these excuses would help her improve. I'm going to count to three, the therapist said. When she got to two, then two and a half, exactly as McKessy's mother used to do, McKessy found herself painfully shifting her legs over the side of the bed. "It was a turning point," she says. "I realized they were the experts, but I had to do the work. And here I am."

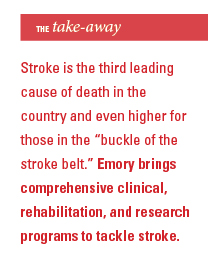

Stroke care is a continuum, from getting patients to the right care to returning them, as well as possible, to families and communities.

Comprehensive stroke centers also have responsibility for helping prevent first or second strokes. That means providing intense clinical follow-up to patients at a multidisciplinary clinic or making sure they are reconnected to medical follow-up in their own communities. It means identifying persons at risk. For example, one Emory program—involving emergency medicine, cardiology, neurology, and radiology colleagues at EUH, EUH Midtown, and Grady—evaluates people who have had a TIA to help them modify risk factors to avoid a full-blown stroke. And it means education on how to recognize and respond to stroke. Every year, Emory stroke nurses provide presentations and screenings in community churches and centers, often at the request of former stroke patients. Prevention also means research to figure out why certain people are at higher risk of stroke. Frankel, for example, leads a national NIH study to evaluate blood biomarkers in at-risk patients. Nahab's research has focused on how nutrition and diet may explain why Georgians, especially African Americans, are at greater risk for stroke.

And like clinical care, much Emory research involves teamwork. "I can't say the word partnership often or emphatically enough," says Nahab, describing his physician, nursing, and other clinical and research colleagues and speaking of the hospitals across Georgia with whom Emory shares patients. "And when I think of how working together is improving care for stroke patients, I always say it with gratitude."

Patients like David Jacobs have their own words of gratitude. When it comes to high-level care and involvement with individual patients, Emory has it down to a T, he says. But if Jacobs knows more than he ever wanted to about stroke care, he acknowledges even more the value of teamwork. To win this game, he knows, is going to take regular people recognizing both the symptoms of stroke and the need for prompt action—and doctors and hospitals working together to get patients to the level of care they need. As legendary coach Vince Lombardi once said, "People who work together will win, whether it be against complex football defenses, or the problems of modern society." EM

Stroke ResourcesTo see a video with the Jacobs family, visit emoryhealthcare.org/strokestory. For more information on the Emory Stroke Center, visit emoryhealthcare.org/stroke/index.html. To learn about support opportunities, contact development officer Katie Laird at 404-712-2211 or katie.laird@emory.edu. |