Why HIV's cloak has a long tail

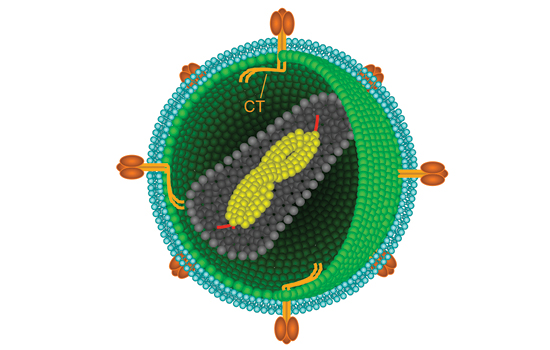

CT = cytoplasmic tail Figure modified from image of HIV virion created by Atuhani Burnett.

Emory virologists have uncovered a critical detail explaining how HIV assembles its infectious yet stealthy clothing.

For HIV to spread from cell to cell, the viral envelope protein needs to become incorporated into viral particles as they emerge from an infected cell. Researchers led by Paul Spearman, Nahmias-Schinazi Professor and vice chair of research in Emory Pediatrics, found that a small section of the envelope protein, located on its cytoplasmic "tail," is necessary for it to be sorted into viral particles. "Many viral envelope proteins have very short tails," Spearman says.

"Why HIV envelope has such a long tail has been a mystery. Now we are beginning to understand that HIV uses specific host cell factors to deliver its envelope protein onto the viral particle. Not only can this help us design better vaccines, it provides a new target for drugs to inhibit HIV." The tail is required for HIV to infect and replicate in the cells it prefers: macrophages and T cells. The long tail is also thought to help HIV avoid the immune system, says Eric Hunter, co-director of Emory’s Center for AIDS Research.

Research dollars

Researchers in Emory’s Woodruff Health Sciences Center received nearly $483 million in funding last year, 93 percent of the university total, with nearly $325 million in federal funding, including more than $288 million from the NIH.