The Evolution of Aimee Copeland

By Mary Loftus, Photography by Jack Kearse

Illustration by Stephanie Dalton Cowan

The zip line wasn't the fancy kind you see at resorts or parks, with safety straps and secure buckles. It was more of the homemade variety—bicycle bars sliding over a dog-runner cable.

|

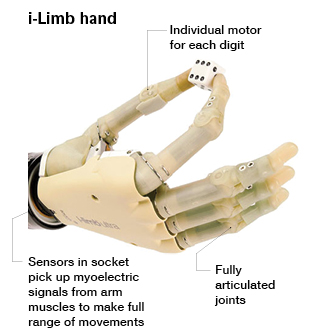

In occupational therapy, Aimee Copeland focuses on learning to perform life skills and daily tasks with her prosthetic hands, such as eating lunch from Moe's: holding the Styrofoam cup, taking off a lid, and picking up a chip. The i-limbs have rotating thumbs, fingers that bend at the natural joints, and "grip chips" that use Bluetooth technology. They respond to tiny movements and chemical and electrical reactions in her residual limbs. Still, learning to control them is a challenge. "It feels like my hand is in wet concrete that has almost completely dried," she says, "and I have to try to move it." |

Aimee Copeland, an athletic, adventurous graduate student in humanistic psychology at the University of West Georgia, was the first one to spot it.

Copeland had just finished her last final for her last class of the semester, and was ready to relax. After working the breakfast shift at Sunnyside Café in Carrollton the morning of May 1, 2012, she was hanging out with friends next to the Little Tallapoosa River, which ran right through the backyard of one of their houses.

"School was out, I was waitressing and bartending at night. I had just gone rock climbing with my boyfriend in Alabama a few days before," she says. "I was living the dream."

The group took turns on the zip line, skimming over the riverbed while hanging about six feet above the shallow water. On Copeland's second pass, the line snapped and she fell onto the rocks below. She could see her leg muscle through the deep, crescent-shaped cut in her leg, and passed out when the ambulance arrived. At the local ER, the wound was stapled up and she was sent home.

Four days later, after increasing pain and several more ER visits, she was on a life-flight to the JMS Burn Center in Augusta, diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis— commonly known as "flesh-eating bacteria"—which was spreading rapidly through her body.

"It could have been any of us, but it was me," Copeland says, in her typical, direct manner. "You can't live your life being paranoid, or in a bubble. The truth is, things like this happen when you least expect it."

A father's pride

Copeland doesn't remember much of the next few weeks, although her father, Andy, kept a heart-rending blog of her time in the hospital.

Her left leg up to the hip was amputated immediately to stop the spread of the infection. She went into cardiac arrest on the operating table but was revived. The first night, her lactic acid levels dipped below the survivable range, she was in renal failure, and a ventilator was helping her breathe.

Her parents and sister kept vigil by her bedside, driving in from their home in Snellville. They played her favorite music, including Bob Marley tunes. Her condition would stabilize, then worsen. By May 8, doctors told them: "Aimee's survival chances are 'slim to none.' She continues to experience a major shutdown of all five major organs."

Against steep odds, Copeland pulled through, her body, aided by medications, drawing resources from her extremities to protect her vital organs. But there was a cost. Two weeks after her left leg was amputated, doctors decided they must also amputate both her hands and her right foot.

Her father told her. First, he let her know she had become a symbol of strength and hope around the country, that AJC Pulitzer-Prize winning cartoonist Mike Luckovich had drawn an editorial cartoon about her bravery, and that messages of support were coming in from friends and fans the world over. "Aimee's eyes widened and her jaw dropped. She was amazed," Andy Copeland wrote.

He told her that more amputations were necessary to save her life, and had her look at her damaged hands. She nodded, then said, "Let's do this."

The comment brought her father to tears. "I wasn't crying because Aimee was going to lose her hands and foot," he wrote. "I was crying because in all my 53 years of existence, I have never seen such a strong display of courage."

After several months of healing, she was moved to the Shepherd Center in Atlanta to learn how to use her electric wheelchair and begin to regain her independence. She went through a period of depression and grief.

And then she got on with it.

"This has made me grateful for what I do still have," Copeland says. "I'm newly thankful for things like my elbows and my right knee."

The tao of eating a tortilla

A little more than two years later, Copeland lives in an apartment adjoining her parents' home, drives her retrofitted van with ease, and uses an iPad to keep up with friends, grad school research, speaking engagements, and rehab appointments like this morning's occupational therapy (OT) session at Emory Rehabilitation Hospital off Clifton Road.

OT focuses on life skills and daily tasks, says therapist Melissa Tober, so the focus here is often on Aimee perfecting the use of her high-tech prosthetic hands. "There are so many everyday challenges, and Aimee faces them with patience and grace," she says.

The prosthetics can be awkward, heavy, and hot. Sometimes they malfunction. This is frustrating for Copeland, since she can do so much without her prosthetics. Sometimes, using them seems more cumbersome than not using them. "But she just perseveres," Tober says.

Copeland smiles wryly. "As much as I love my parents, I don't want to live with them for the rest of my life. I want to move out and be independent," she says, "so this is all pretty important."

Today's session focuses on eating a lunch Copeland has brought with her from Moe's—a burrito, a drink, chips, guacamole. "I want to get more confident about eating in public," Copeland says. "Eating is such a messy thing anyway."

She's had some issues with her prosthetics, with the fingers sticking on some of her finer movements and her thumb hyperextending.

Rob Kistenberg, co-director and coordinator of prosthetics at the School of Applied Physiology at Georgia Tech and an adjunct faculty member in Emory's Division of Physical Therapy, is sitting in on the session. He's making minor adjustments to her prosthetic hands, the i-limb ultra revolution manufactured by Touch Bionics in Scotland, on his computer.

Copeland gets annoyed when people think her "bionic hands" are controlled by her mind—that she can just think what she wants them to do, and they will automatically do it. "It's a lot more complicated and harder than that," she says. "It feels like my hand is in wet concrete that has almost completely dried, and I have to try to move it."

Basically, she says, she concentrates on moving the muscles of her phantom hand, which translates to tiny movements and chemical and electrical reactions in her residual limbs that signal her prosthetic hands. "Sometimes it feels like bending my wrist backward, or a double-pulse, or flicking water off my fingers," she says.

|

Stairs and ramps are difficult to navigate with two prosthetic legs, requiring incredible strength and balance. Building up her endurance is a large part of physical therapy, and Copeland can do 200 crunches in seven minutes, as well as 400 leg lifts, side planks, push-ups, and more. "It's all about the core," she says. "I can do more crunches now than I ever could before, but I'm still sweaty and exhausted after an hour or so of walking." |

These signals are very subtle, Kistenburg says, but electrode sensors placed in the forearms of her prosthetics are sensitive enough to read them through the skin.

Tober encourages Copeland to start unwrapping the burrito, and the aluminum foil—which has stuck to the warm tortilla shell—provides the first challenge. After several attempts, Copeland is able to separate the foil from her veggie burrito.

"A lot of OT is just troubleshooting," says Tober. "Aimee will tell me about something that is frustrating her, things she's having a hard time doing, and we'll brainstorm different ways to make them easier."

Copeland appreciates Tober's female sensitivity as well. "I was talking with another therapist, who was male, about wanting to be able to put my hair back in a ponytail, and he said, 'Just cut your hair,' " she says, shaking her head in disbelief. "No offense, Rob."

"None taken," says Kistenburg, laughing. "I have daughters and am the sole male in my household, so I can do ponytails. I understand the importance."

Prosthetic hands need different types of coverings and accessories to make them practical—touch-screen friendly fingertips, for instance, to be able to use devices like tablets. "My iPad is my connection to the world," Copeland says. "I use it for school, my papers, all my books, social networking, email. It controls the lights, fans, and thermostat in my house and is my remote control."

Today's efforts to eat the Moe's meal, including opening the chip bag, taking out a chip without breaking it, and lifting a Styrofoam cup without crushing it, hinge on fine-tuning her grip. This is made immeasurably harder without the sense of touch. Kistenburg experiments by programming several different options into the prosthetic hands—there are 24 grips available.

"One of the hardest things about this is that I love cooking and cleaning and entertaining. I'm kind of OCD about it," says Copeland. "I like to nurture other people, not be the one asking for help."

Forward momentum

|

Prosthetist Rachel Schmidt of ProCare Prosthetics adjusts Copeland's leg, which has a microprocessor in the knee with angle and load sensors that analyze her gait while she's walking as well as how much weight she puts on her toe and heel. Alignments are made by linking the knee through Bluetooth to the computer, but Schmidt can also make manual adjustments. |

Copeland remains active—she's been kayaking, does strength training, and has even been back on a zip line. And she's looking forward to taking up more sports, such as horseback riding and cycling via a custom bike.

But mostly, she wants to spend more time walking and less in her electric wheelchair.

"I don't really need my prosthetic hands, I have silly, creative methods I've devised," she says. "But I can't walk without legs. That's my main goal—to get rid of the obstacles this wheelchair produces."

During a physical therapy (PT) session at Emory, she works on going up and down steps, stairways, and ramps with physical therapist Beth Fordyce in the hallway of the Rehab hospital, wearing her leg prosthetics and blue Puma sneakers.

"I find it's better when I don't stare at my feet," she tells Fordyce, taking careful steps down the stairs. "It feels like if I get too much forward momentum, I could fall."

"You've got to train your muscle memory," says Fordyce. "But steps are different heights, so it's hard to know what to expect."

One of Copeland's prosthetics includes a waist strap and an artificial hip joint that mimics human hip movement; the other fits onto her calf just below her knee. Gel liners, medical-grade silicone, and five-ply and three-ply socks keep the skin from chafing, in theory, but dealing with blisters and bone bruising is unfortunately still a common occurrence.

Fittings are always a challenge, says Copeland's prosthetist Rachel Schmidt of ProCare Prosthetics, due to the fact that leg prosthetics are weight bearing, the complications of joints, and scar tissue.

Copeland's prosthetic has a microprocessor in the knee with angle and load sensors, which analyze her gait while she's walking as well as how much weight she's putting on her toe and heel. "When we're initially aligning, we link the knee up through Bluetooth to the computer," says Schmidt. "But we also can make manual adjustments."

Copeland's PT appointments often involve a killer workout in the hospital's gym. "It's all about the core," she says. "I can do more crunches now than I ever could before, but I'm still sweaty and exhausted after an hour or so of walking."

She isn't kidding—Copeland can do 200 crunches in seven minutes, as well as 400 leg lifts, side planks, pushups, and almost any other core-strengthening exercise you can think of. This has been the focus of her PT at Emory for several years, since much of Copeland's mobility—getting in and out of her wheelchair, walking on prosthetics—relies on her abdominal muscles.

"Being outdoors and adventurous has always been vitally important to me, and I'm not going to compromise on that," she says. "I'm not going to be going on five-mile hikes anymore, but I don't want to be stuck inside either."

Into the wild

In Copeland's dreams, some of the time she is like she was before, and other times, she has been through the amputations. "My essential 'self' is the same," she says, "but I'm definitely not as idealistic as I used to be. I've become hardened by the realities of life. It's not all puppies and rainbows anymore. I've learned to cultivate deeper strengths."

Copeland believes, more than ever, that it's essential to teach girls that they are more than just their physical bodies and appearances. And she now has the platform to do that: She has appeared on the TODAY Show, CNN Headline News, and Good Morning America and receives constant invitations to be a motivational speaker, especially to student groups.

She drives to Valdosta State once a month to meet with professors in her second graduate program and has started an internship in social work. And she does lots of advocacy work, serving on the advisory council for Tools for Life and the board of Friends of Disabled Adults and Children, pushing for accessibility and inclusion.

"I was super spoiled before. I relied on being charming and attractive to get what I wanted. Now, I'm more mentally focused. I have to be more clever, to use my intellect," she says. "But my experiences have also bred compassion. When you lose a large part of your body, you have to go deeper."

One of the reasons she was pursuing humanistic psychology at a graduate level, even before the accident, was to investigate the purpose and meaning of life on her own spiritual quest. Now, she says, it has become essential in giving her the ability to deal with what she's facing. "My whole life has led up to this moment," she says. "That's never been more clear."

Copeland is studying eco-psychology and wilderness therapy, with the intent of bridging the gap between nature and accessibility. After she graduates in 2016, she intends to become a licensed clinical social worker and start a private practice.

Her larger vision is to get "a big chunk of natural land," and build a sustainable, off-the-grid community open to people of all ages and abilities, with wide trails, adaptive yoga, outdoor sports, raised campsites—and a staff of nurses, therapists, and instructors, where all visitors' needs would be met.

Already, people have contacted her about donating land. "I want to create a place where the wilderness can be available to anyone," she says. "And I will live there. And it will be totally awesome."

From bronze cast to bionic limbs

|

|

In ancient Egypt, prosthetics were developed more for cosmetic reasons than for functionality. Some mummies had prosthetics made of leather and wood and were buried with them so they would be "whole" in the afterlife. The first true prosthetics, in the sense that the term is used today, were made during the Greek and Roman period, usually to replace limbs lost in battle. These were often bronze or iron, with a wooden core and leather straps. French surgeon Ambroise Pare's mechanical hand, "Le Petit Lorrain," from the 16th century, was operated by catches and springs. Now, prosthetic hands have motorized digits and look and move more like natural hands. For example, i-limbs can be programmed to individual specifications and controlled by mobile apps. Prosthetic legs have made similar advances, with robotic legs, sports legs designed for speed and impact—from running blades to swimming fins, and high-fashion designer legs. "Bionic" limbs can be moved by neurosignals sent from existing muscles.