Guidelines for Treating Cholesterol

By Quinn Eastman

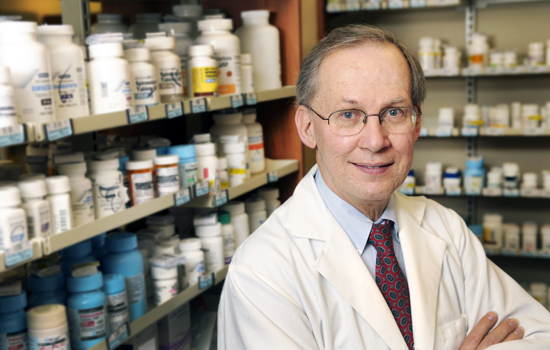

Dr. Peter W. Wilson Photo by Jack Kearse

Newly revised guidelines for treating cholesterol to reduce cardiovascular disease risk were released in November by the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC). The new guidelines de-emphasized achieving target numbers for LDL-C (low density lipoprotein cholesterol), the harmful form of cholesterol. Emory preventive cardiologist Peter Wilson served on the AHA/ACC task force that formulated the new guidelines. He drew on a wealth of research experience, including 20 years as director of laboratories at the Framingham Heart Study in Massachusetts, as well as clinical experience at the Emory Clinic and the Atlanta VA Medical Center Lipid Clinic.

Why did an update become necessary?

Cholesterol-lowering medications had become more potent over the past decade. More information on their safety and efficacy was available, but that evidence had not been integrated into the recommendations. Many statins have recently gone off patent, so their cost has gone down—atorvastatin [Lipitor] is a prominent example of a lipid-lowering drug that now costs much less. And we needed to evaluate the results of clinical trials involving statins—statins vs. placebos, low dose vs. high dose, statin plus a second drug vs. statin alone.

In addition, several questions about testing and evaluation had come up. Doctors want to know: "How low does cholesterol need to go? Do you need do a CRP (C-reactive protein) test? What about coronary artery calcium (CAC) testing?"

The NIH Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute directed us to use the Institute of Medicine approach, which is sort of a "guideline for guidelines." They have a hierarchy of evidence, with randomized controlled clinical trials carrying the greatest weight, and a mandate to limit the number of recommendations that are "expert opinion."

What is considered expert opinion?

For example, the advice to get some patients' LDL-C below 70 mg/dL. When that was promulgated in 2004, there was no hard evidence for it. There was one study with data on people who had LDL lower than 70 mg/dL, where you could infer some possible benefit. A lot of providers jumped on that and said, "I'll get everybody under 70 if I can! If it's safe and tolerated, why not?"

How will the new guidelines affect patients with different profiles?

Let's take a high-risk case—a middle-age male smoker with high blood pressure. His LDL-C level is 130 mg/dL. This is an "average Joe" LDL. He had a heart attack and is sent home from the hospital on a statin. Before, the goal was to get the patient's LDL-C below 100 mg/dL. The doctor would say, we'll see you in six weeks. When the patient came back, the doctor would ask about statin side effects and look at the LDL-C levels. If there had been some progress, the patient would be told to keep up the good work. But this reflects a short-term focus. Sometimes you see people at six months post-heart attack and they're not on their medicines. Patients ask: "Is this lifelong?" Well, yes, unless there's a big change. Unless you become a low-fat, low-cholesterol vegetarian, you're probably not going to be able to make great progress in lowering LDL-C without medicine. Now, let's take that same man under the new guidelines. An LDL-C of 130 is clearly too high, so he'd be put on a high-potency statin. A post-heart attack patient would probably get rosuvastatin (Crestor) or atorvastatin (Lipitor). If he can't tolerate either of those, we'll move on to other options.

One of the biggest changes is that there are no hard targets for patients' LDL-C. How will you determine success?

The key element of success is that the patient takes the medicine. If that same patient we just talked about comes back in a few months and his LDL-C level is 140 mg/dL, I get the feeling he is not taking it. Some experts say they want patients to take medicines and see if LDL-C gets better. I say, probably the most important thing is for you to take the medicine and follow other preventive advice like cutting down on smoking, eating a heart-healthy diet, and reducing weight if needed.

Let's consider another patient, someone with different risk factors. She is diabetic and a smoker, but has not had a heart attack. All diabetics are now considered to be at high risk for cardiovascular disease, especially if they are over 40. Should we wait six months before giving lipid medication? No, we treat her more aggressively.

Now let's take a trickier case. We have a 50-year-old, no risk factors, but a family history of heart disease. He's concerned. The calculated 10-year risk is about 5%. LDL-C is 110 or 120 mg/dL. He might say, "Doctor, what you say is comforting but I'm wondering if we're doing enough." This is where you have the risk discussion, and where some of the newer tests (CRP and CAC) come into play as discriminating factors. I may bring up a low-dose statin as a preventive, perhaps pravastatin 40 mg per day. It's very easy to tolerate.

Why not just take a daily, low-dose aspirin?

It's not clear that you need to take both aspirin and a statin. Most of the trials that showed the benefit of taking a daily aspirin were completed before the modern era of statins. There is a trial going on at NIH that is evaluating the role of aspirin in the elderly.

One of the main effects of the new guidelines is that there will probably be less cholesterol testing in patients on lipid medications. In the past the patient would return to clinic every three months and progress would be marked by looking at the patient's LDL-C level. Now, the most important thing is to keep taking the medicine, as tolerated.

Are there diminishing returns with cholesterol-lowering drugs after some point?

Yes, for those with LDL-C 70 compared to 90 mg/dL. The data suggest that lower is better for your cardiovascular health, but the evidence is not as strong as some physicians would like to think. The next frontier is LDL 40 compared to 80 mg/dL.

An LDL-C of less than 50 mg/dL is more achievable than ever before. There are new medicines coming online, such as PCSK9 inhibitors, which can accomplish that. The question is, is there a benefit? Is it appropriate? We don't know yet.

Are there any gaps in the guidelines?

Statins are of little or no benefit where there is already lots of calcification. You see that in people with calcified aortic valves. You also see it with patients who are on dialysis because of kidney disease. When you see the more calcified lesions, it's probably too late for statins. Statins won't do harm, but there may be little benefit.

If there is a gap in the guidelines, it's what to do with young people with familial high cholesterol levels. What do I do with a 20- or 30-year-old with very high LDL and no other risk factors? They should be on very aggressive treatment. It may seem obvious, but often physicians will give them one medicine and will stop there. These patients really should be referred to a specialist.

Media coverage of the new guidelines may have given the public the impression that almost everybody should take statins at some stage in their lives. They do identify more people to take statins because of the risks and benefits. We knew that in 2001, but the treatment threshold was put higher, somewhat arbitrarily. At that time, recommending statins was more apt to be considered inappropriate because the cost of treatment would be substantial. That's no longer the case. In terms of cost, statin therapy is starting to look very similar to blood pressure control, which can be done inexpensively.

In the new guidelines, did you reach a conclusion about the value of tests such as CRP and coronary artery calcium (CAC)?

These tests are a research issue that many of us are interested in, but it's still unclear whether we need to have them done for every patient. I would advise patients not to run out and get a coronary artery calcium test. Cost is an issue and, with CAC scoring, radiation exposure is a concern if the patient has the test multiple times.

Stepping back, some of these tests may be helpful for patients with intermediate risk. They may help us decide whether to treat more or less aggressively. If you're having a risk discussion with a patient about family history and other risk factors but the patient is reluctant, that's where additional testing might help and a positive test might tip the balance toward a more aggressive treatment.

So, how long should a patient be on statins? What age should you start?

It's hard to say because there are very few heart disease events in men younger than 45 or women younger than 55.

Let's talk about statin side effects. What are the most common ones?

Between 5% and 15% of people who take statins will get muscle aches. It's not like cramps that appear at night—it feels like soreness after exercise. There is no blood test to shed light on this symptom, and there are no obvious signs of muscle inflammation.

The three main items to monitor for safety are muscle symptoms, liver enzymes, and creatine kinase for kidney function. The rule of thumb is this: monitoring is good to do when starting treatment or when changing dose. You don't need to do the tests all the time, but maybe once a year is appropriate. More frequent monitoring may be needed for some of the newer drugs.

The risk of developing diabetes while taking statins is real but relatively small: 1% or 2% greater risk. It is dose dependent and related to the potency of the statin. You have to balance that against reducing the risk of a heart attack.

What should be done if the patient does not tolerate the statin medication?

There are a lot of statins you can try. But it's problematic if someone needs a high-potency statin over the long term. Let's take someone who was sent home with a prescription for atorvastatin (Lipitor) 80 mg/day. He tries it for three weeks and stops because of aches. Doctors will probably try switching him to a different drug. But an overlooked strategy is to simply use the same statin at a lower dose. Patients can take the statin every other day, and gradually work their way up to a dose they can tolerate. Plus, it's OK to take a statin holiday for a few days when, say, you have the flu and feel horrible.