The Lifeline

By Elizabeth Johnson, Medical illustrations by Satyen Tripathi

Megan Blay thought she knew exactly how the birth of her second child was going to go.

Megan Blay thought she knew exactly how the birth of her second child was going to go.

Her natural water birth would be a sort of redemption after having her labor medically induced with her firstborn, Lola.

In late summer 2015, Blay was fully immersed in the details of her birthing plan — she had selected a hospital that supported water deliveries, near her family's home in Acworth, Ga., and her husband, Adam Linville, and her physician would be the only people in the delivery room with her.

At a regular checkup midway through her second trimester, however, she learned that something wasn't quite right. The doctor saw an abnormality on the ultrasound near the fetus's mouth. His initial suspicions were cleft pallet or cystic mass, but he recommended a follow-up with a specialist.

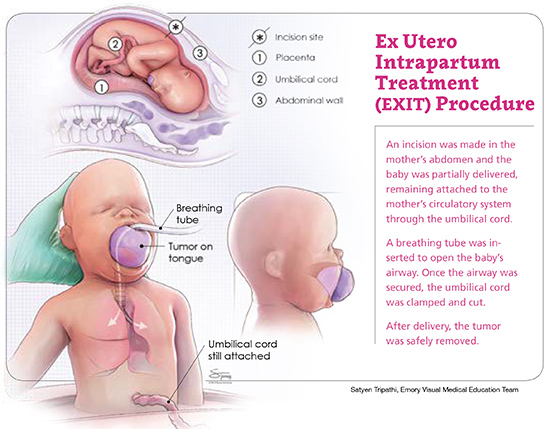

He also brought up an ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure as a possibility for Blay's delivery, if in fact there was a large mass blocking her baby's airway.

Blay had never heard of it. She went home and frantically researched EXIT procedures online, spending days looking through online groups and comment boards and finding mothers who had been through the procedure.

Babies born using EXIT are partially delivered — just their head and shoulders — through a standard cesarean section. The bottom half of the baby stays inside the uterus, continuing to receive oxygen through the umbilical cord and warmth and protection from the placenta. This allows pediatric otolaryngologists to unblock the baby's airway and get them stabilized enough to complete the delivery. Throughout this process, the mother is under general anesthesia.

"I did the research and then immediately put it in the back of my mind," Blay says.

She found a maternal-fetal specialist in Atlanta and scheduled an appointment to get a second opinion. After appointments with the maternal-fetal specialist and another Atlanta doctor who was natural-birth friendly, it was determined that her baby likely had a cyst around her mouth that could safely be drained and treated following a natural birth.

To err on the side of caution, however, she was encouraged to visit Emory physicians at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta Egleston so its team could review Blay's MRI and ultrasound.

Not wanting to take chances but with renewed optimism, Blay made the 37-minute drive to Atlanta one more time for an appointment with pediatric otolaryngologists Steven Goudy and Kara Prickett. At this point, it had been 16 weeks since the initial discovery of her baby's suspected cyst and Blay was well into her third trimester.

At this appointment, she received the most devastating news yet. The fetus's airway was blocked due to a mass that had formed on her tongue. The pediatric surgeons began planning for an EXIT procedure.

"I left that appointment feeling very, very emotional," Blay says. "I resented the doctors because that was not the delivery I wanted. The birth plan I had worked so hard to develop with my obstetrician was perfectly simple but there were a lot of little things that I really, really wanted. I realized I only had a couple of weeks to let all of these things go."

With four weeks left until Blay reached full term, Goudy and Prickett immediately started meeting with a team that included maternal-fetal physician Jane Ellis and more than 30 other physicians, nurses, anesthesiologists, and technicians that would be needed to successfully plan and carry out the delivery.

"Once we all met as a team and decided that yes, this is a life-threatening delivery for the baby and obviously for the mom as well, then we started talking about managing the breathing, because that's really the whole reason for the EXIT procedure," Goudy says. "We had to discuss how we maintain the baby on the placental circulation, providing oxygen to the fetus for as long as we can, so it gives us a window of time to breathe for the baby, once he or she is born. We're talking about a finite time frame of 15 minutes to 40 minutes at the most."

Support system

A mother and fetus are part of an efficient exchange system, in which the placenta — considered a temporary organ made up of blood vessels and membranes — transfers oxygen and nutrients from the mother's blood to the fetus, and waste products from the fetus to the mother. The EXIT procedure takes advantage of this system as long as possible, allowing babies with malformations of the mouth, tongue, throat, or trachea to continue receiving oxygen and nutrients from their mother during the operation.

Fortunately, the Emory team had recent experience in performing this rare and highly specialized procedure — just a few months earlier, they had successfully delivered another baby with life-threatening airway issues. Ryan Montgomery was diagnosed in utero with blockage atresia of his trachea and his airway was not developing properly.

While planning the Montgomery operation, the pediatric and obstetric surgeons determined that Grady Memorial Hospital was the best place to perform an EXIT procedure delivery due to its larger operating rooms, designed to handle acute trauma patients. "Grady is well positioned because its NICU takes care of very, very sick babies," Goudy says. "In Ryan's case, he had to be resuscitated before we transported him to Egleston. That's one of the complexities of how we're caring for these patients — our hospitals are not next door to each other. Having said that, I think we have a pretty good system set up."

Medical team members were preparing for baby Montgomery's birth when his mother went into labor prematurely. They performed a quick dress rehearsal in the operating room at Grady that morning.

An intricate dance

Planning for EXIT procedures requires an intricate choreography — having the proper equipment at the ready and coordinating the care of two patients simultaneously. The mother is the primary patient and the baby is second.

"Each patient has a team acting as their spokesperson," Prickett says. "We had 35 to 40 people in meetings ahead of both of these deliveries, focused on how everything would work. We decided who was going to direct traffic in this packed operating room. The neonatologists were also involved because they're the ones responsible for the baby's care once we have secured the airway and fully delivered the child."

Grady had the equipment and resources needed to monitor the mother's condition before and after the procedure, as well as nurses who are used to postpartum care. But because Grady is not primarily a children's hospital, the team had to borrow surgical equipment from Children's at Egleston to care for the babies immediately following birth.

The vast majority of physicians at Grady have Emory faculty appointments and almost all of the physicians at Children's at Egleston are Emory faculty, so there were institutional connections throughout the system that made the complex series of handoffs flow seamlessly, Prickett says.

"The neonatology team that staffs the NICU at Grady is the same group that cares for the babies at Children's at Egleston," Prickett said. "It's just a matter of who is scheduled to be where on any given week, but we were all in the same meetings, planning for the delivery of both the Montgomery and Blay babies.

During this period, Prickett and Goudy also spent time with Blay and her husband, showing them around the facilities at Egleston and helping them get as comfortable as possible with their baby's new delivery plan — a plan that was likely the baby's only chance for survival.

"I really only had a week to understand everything that was happening," Blay says. "I had been in denial from the first doctor's appointment when an EXIT procedure was mentioned. I think that made the shock factor a little worse; I had not prepared myself mentally and I just kept asking, 'Why is this happening to me? Why is this happening to my child?'"

She vividly remembers the night she and her husband arrived at the hospital. She was 39 weeks along, but Ellis and the obstetrics team had determined that it was time. She was scheduled to deliver the next day.

"It was extremely nerve-racking," Blay says. "I felt a little bit like a test subject because there were so many people coming in and out of my room to ask questions— anesthesiologists, the pediatric surgeons who were going to perform the surgery on my daughter, nurses, even some people who were just curious about my case."

Blay and her husband attempted to sleep that night but she remembers the clock's slow creep toward 6:00 a.m., when nurses began coming into the room. She was instructed to clean her body with sterilized wipes in preparation for the surgery.

The rest of the day was nothing more than a blur. "I initially didn't want to be put under general anesthesia. I fought that a little bit but the doctors told me we had to, in order to keep my heart rate stable and anxiety levels normal," she says. "Looking back, I'm so glad that I wasn't able to see everything because of how intense the surgery was."

"Delivery via EXIT procedure is really different because you're using the circulation of the mother, anticipating that there is going to be a problem once that is no longer available. You're forced to make decisions rapidly." Dr. Steven Goudy, otolaryngologist

Busy birth day

Emma Linville was born just after 9:00 a.m. on January 20, 2016, by cesarean section. While Emma was still being supported by the placenta and the umbilical cord, half in and half out of her mother's abdomen, Goudy and Prickett pushed the growth in her mouth aside so they could see her larynx and insert a breathing tube.

"The mass was contained within the front part of the tongue," says Prickett. "We pulled it forward and that left room to pass the breathing tube behind it and down into the airway."

If they had not been able to safely insert the tube, Goudy says, they would have performed a tracheotomy on the baby to bypass the blockage.

Ellis, who led the mothers' care team in both of the recent EXIT procedure cases at Grady, said it is a sight to see the delivery/operating rooms for these procedures. "It takes a village," Ellis said. "At least 30 people were involved, ranging from equipment representatives, operating room staff, and ultrasonographers, to surgeons, nurses, and more." Other key members of the EXIT procedure team included Matthew Clifton, surgical director for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for Children's at Egleston and associate professor of pediatric surgery at Emory, and April Landry, assistant professor in Emory's Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery.

"Delivery via EXIT procedure is really different because you're using the circulation of the mother, anticipating that there is going to be a problem once that is no longer available. You're forced to make decisions rapidly," Goudy says. "You have to have somebody working an IV for the baby so we can give them medicines to make them not breathe. As soon as the baby wakes up and starts breathing, the placental circulation shuts off. It requires coordinating all of those things in a rapid sequence."

Immediately after Emma was delivered and stabilized, she was taken from the operating room to the Angel II Neonatal Transport ambulance and rushed to Egleston, where a medical pediatric team waited to remove the golf ball-sized teratoma from her tongue. (It was only after Emma was delivered that doctors officially diagnosed the mass.)

Time to heal

Nearly a year later, Blay still tears up remembering the flood of emotions from that morning. She would not see her newborn for two days while she lay in a recovery room at Grady.

Blay's husband, Adam, and his parents stayed with Emma while Blay was at Grady with her parents.

"While those two days were extremely hard, I ended up being grateful for that time," Blay says. "It gave me the opportunity to deal with the entire process, the emotional and physical pain that I had undergone. Adam visited, of course, but it was nice to be able to tell my story to the nurses. Every time a new nurse came in they would ask where my baby was, and I was able to talk through everything."

Once Blay was cleared to leave the hospital, she joined the rest of her family at Egleston, where they stayed in rooms reserved for the parents of newborns in the NICU. They left the hospital only briefly over the next two weeks to go home and nap.

"There was a point where I just really needed to get away from the beeping and other sounds of the hospital," she says.

They were fortunate to live within driving distance of Egleston. According to the pediatric surgeons, the process leading up to and following an EXIT procedure often requires families to relocate for months to be near their care team.

"It's a big deal for people, to be able to keep the burden of this procedure and the recovery process close to home," Goudy says. "With the resources of Emory, Children's, and Grady all in one place, there is no reason Atlanta families should not be able to have access to the best possible maternal-fetal care available."

Emma's recovery went well. Doctors received test results confirming that her tumor was benign. She remained on a feeding tube for three weeks, at which point Blay was able to begin breastfeeding her.

Prickett had to explain to Emma's parents that her mouth would remain permanently open for a short period, because that's how it had developed.

"You would never guess by looking at Emma now that she had this massive tumor on her tongue at birth," Prickett says. "She's doing great, and a year later the follow-up is very minimal for her. We just want to make sure that nothing grows back where the tumor was."

Blay says she never let herself consider the worst-case scenario, but looking back she realizes that Emma is lucky to be alive.

Blay says she never let herself consider the worst-case scenario, but looking back she realizes that Emma is lucky to be alive.

Her early diagnosis, and the skill of the medical teams, made what was a difficult, risky situation go as smoothly as possible. For this, she and her family are extremely grateful.

"Emma is such a playful, outgoing baby. She loves to get into everything and wants to put everything in her mouth. She's crawling really well and one of her favorite things is to be outside, playing in the grass with her big sister," Blay says, holding her daughter close as they sit in a favorite chair, with Emma peacefully nursing.

Finally, Blay realizes, everything is exactly as she had envisioned it.