Animal Care During COVID

As part of its research mission, Emory cares for thousands of animals across the enterprise—at Yerkes National Primate Research Center alone there are about 5,000 mice, rats, and voles, and 3,400 nonhuman primates split between Yerkes’ 25-acre main campus and its 117-acre field station in Lawrenceville, Georgia.

These animals require many human caregivers, from vets and vet technicians to behavioral management specialists, resource managers, and animal care technicians, as well as the researchers and research assistants whose work translates into new therapies, vaccines, and discoveries that aid health and well-being—including research on COVID-19. “Our biggest challenge has been working through reduced staffing, which we had to facilitate initially because we split our groups into teams so we would not expose all of our personnel at the same time,” says veterinarian Joyce Cohen, associate director of the Yerkes Division of Animal Resources. “Now it’s because of virtual learning considerations for our employees’ children.”

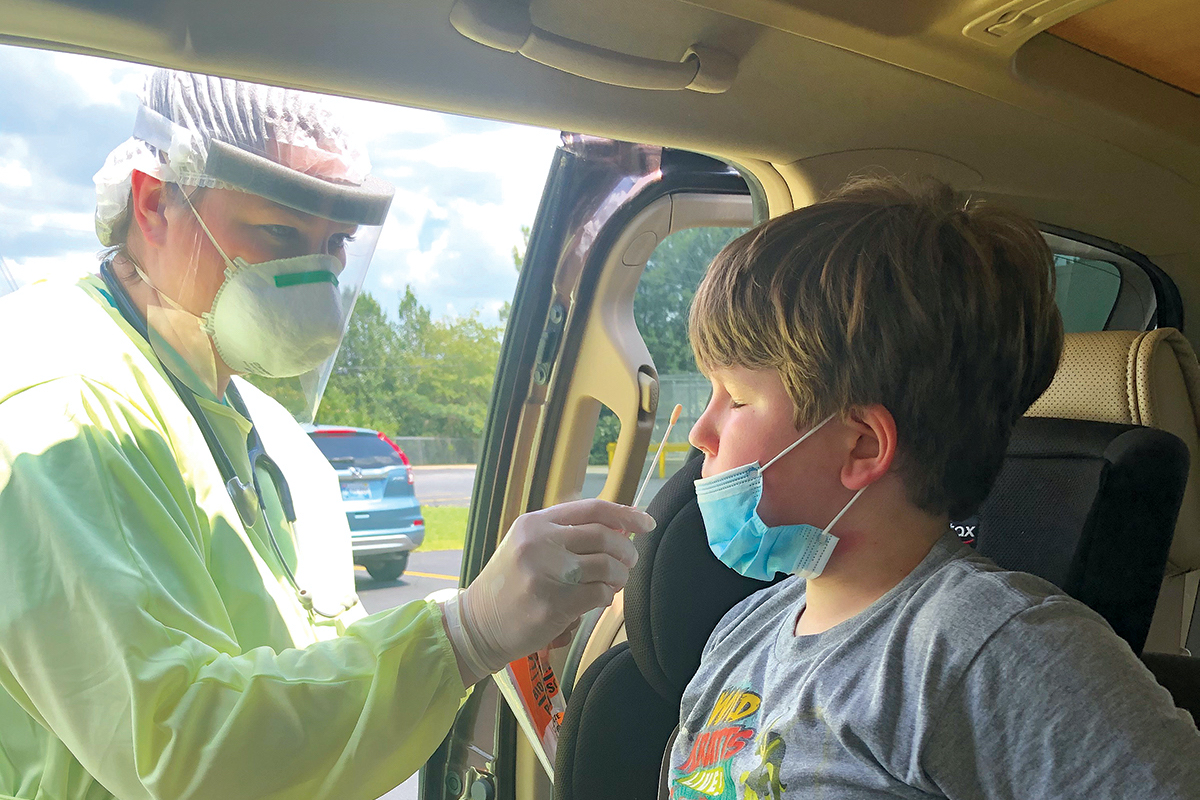

Everyone stepped up to the plate, working doubly hard, says Cohen, associate professor in the division of psychiatry and behavioral science at Emory’s School of Medicine. “And they are all wearing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) every time they work with the nonhuman primates, to protect the animals from diseases we carry as well as to protect staff from natural diseases the monkeys carry. Even before COVID, this was the case.”

During the height of the pandemic, Yerkes tamped down some of its research, and the only new studies accepted were COVID-19 research. But staff tried to preserve as many ongoing studies as possible. “Our Biosafety Level 3 lab is up and running, which takes a tremendous amount of time and energy,” Cohen says. “We always feel there is a need for animal research, and an emerging infectious disease is a great example of why we still need to have it.

Nonhuman primates are very good models for emerging infectious diseases like COVID. It is absolutely critical to have these animals ready so we can jump right on vaccines and treatments.”

The field station’s monkey colonies also require constant, careful tending. For example, the rhesus macaques—Yerkes’ primary species—came into baby season during the pandemic, which meant a lot of work for caregivers. Animals are housed in pairs when possible to make sure they have a social partner. At the field station, where the behavioral research social colonies are housed, workers monitor social interactions of large groups, from five to 150.

Chimpanzees can no longer be used in research so Yerkes’ chimps were “retired,” but Emory still provides them the same level of care while it pursues donation opportunities. “Chimps are notorious for being susceptible to human respiratory infections, and many of them are geriatric at this point,” Cohen says. “We are doing our best to protect them.”

Emory School of Medicine researchers have ongoing studies involving a plethora of animals kept in vivariums and research buildings across campus, including 75,000 mice plus rats, pigs, sheep, rabbits, guinea pigs, hamsters, gerbils, songbirds, voles, spiny mice, zebrafish, and lampreys. “Our challenges are centered around caring for animals in nine housing locations,” says Michael Huerkamp, director of the Division of Animal Resources and professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Emory School of Medicine.

Certain species have unique attributes that make them valuable for specific lines of scientific inquiry, Huerkamp says.

“We’re fortunate to have dedicated pros on our teams, with longevity and specialized skills,” he says. “This work is vital to the mission of the university. We also want to get everyone to the other side of COVID, staying healthy along the way.”—Mary Loftus