Of Clocks and Covid

Losing my mother to COVID-19 made me realize the value of health care professionals who saw her as more than a number.

Call it the effect of growing up without health care in a large farm family of limited means: my mother avoided doctors, fearing that a visit for one ailment would yield another, until one’s pockets were empty and patience at an end.

In 2006, her worst fears were realized when, experiencing acute back pain, she was seen at Emory University Hospital on New Year’s Eve. Abnormalities were spotted on her lungs, liver, and kidneys. Though she voiced myriad complaints about the doctors’ motives, I somehow got her to take the follow-up tests, all of which turned out fine.

At the age of 80, in 2013, my mother was sent by her assisted-living facility to the nearest hospital—not one owned by Emory—for a UTI. While she was there, a doctor breezed in, put his hand on her forehead, and said to me as if she were not in the room, “You can tell from the shape of her skull that she has dementia now.”

She might not have heard him or chose to ignore him. The news rocked me. And, to be honest, I felt a bit skeptical for my mother: who gets to say that you have dementia based on the shape of your skull?

But I had to admit, my mother had been experiencing some cognitive decline, noticeable to those closest to her. So, I prevailed on her to become a patient at Emory’s Cognitive Neurology Clinic (CNC).

For me, the merits of beginning treatment were obvious: I knew that rigor and science would prevail along with—sorry, Mom—that pesky penchant of the doctors to consider every possibility.

The early days of her treatment there were a little rocky: my mother hated drawing clocks (a diagnostic test for dementia) and had the same sinking sensation that everyone experiences when answers to test questions don’t come easily—or at all.

Two things helped her turn the corner to acceptance and, eventually, appreciation. As our family archivist, she wished to hold onto that title as long as she could, wanting to remember what the rest of us had forgotten. There’s power in such a skill, and she liked that.

The other piece of good fortune was that we were paired with a nurse practitioner, Stephanie Vyverberg, who lit up my mother’s world. Her professional competence was obvious and reassuring to me. For my mother, it was her compassion. My mother reveled in being directly addressed by Stephanie, who often held her hand as they talked. No visit was rushed; she gave my mother the time and space to be heard.

Stephanie did what my mother, for so long, believed those practicing medicine don’t do: she treated the whole person. And in being willing to travel that road, what she got from my mother was a combination of sweet and salty.

By this time, my mother resided in a skilled nursing facility where chasing down a nurse was a challenge and getting time with a physician even more elusive. In this environment, the value of “a Stephanie” came into sharp relief. As my mother’s trust deepened, she started saving up things to tell Stephanie—things that, despite our being close, she didn’t tell me. At one appointment, in response to gentle questioning, my mother confessed her struggle with depression. She cried openly—my tough-as-nails mother for whom tears were rare.

More than any medicine—and Stephanie also made many good calls on that front, enhancing my mother’s quality of life—her greatest gift to my mother was the assurance that she was not alone.

All that changed with the advent of COVID-19, which left my mother, like so many residents of skilled-nursing facilities, alone and deprived of all visits or contact with the outside world.

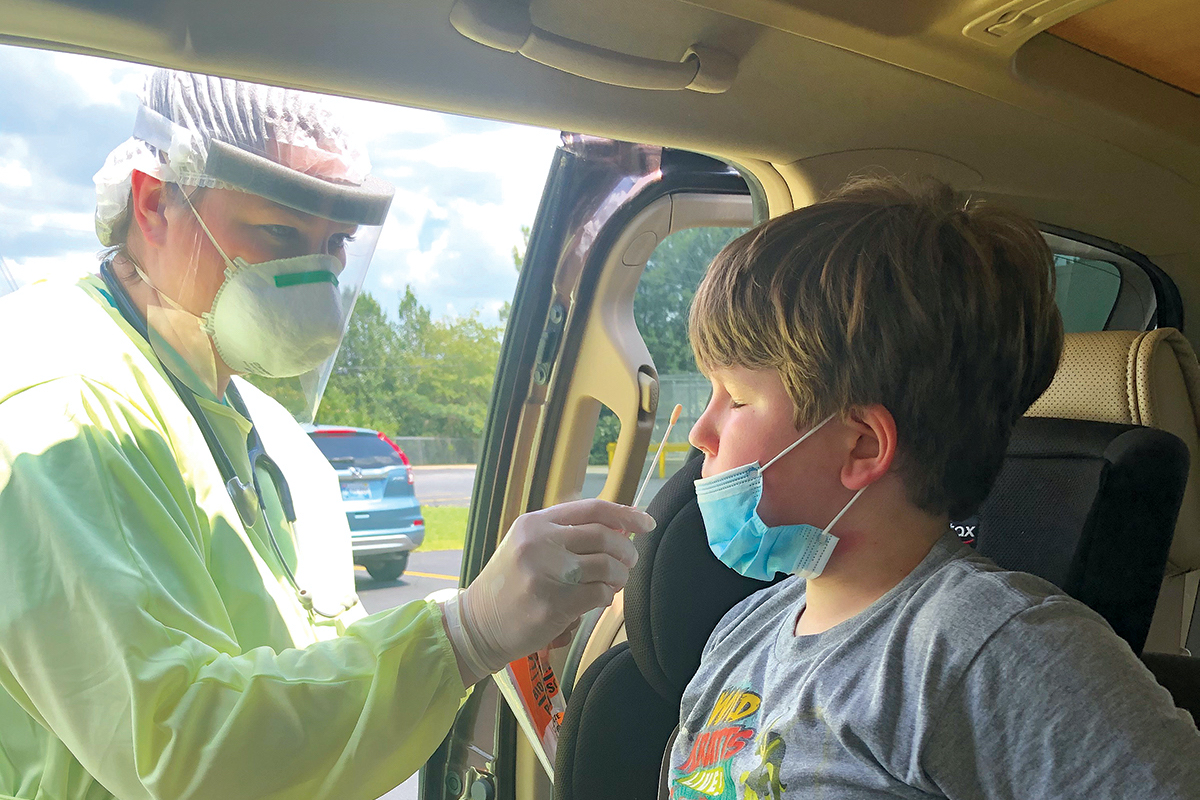

In late June, I got a call from a nursing supervisor; my mother had been exposed to COVID-19 by a staff member. Many days later, my mother’s nurse finally got back to us that she had tested negative for the virus. Then, just two days before she died, I got a call saying she had been tested again and was positive.

For my sister and me, the likelihood that she had the virus before it was confirmed had become abundantly clear: she was out of breath, running a low-grade fever, and having nausea and diarrhea. Her speech had become degraded, and the only people with the patience to understand her were my sister and me.

Yet we were on the outside looking in, facing what increasingly felt like silence with regard to my mother’s fate.

Regarding cases, my mother’s facility had seemed to be doing well until, in an instant, it wasn’t.

My sister and I frequently went online for the Georgia Department of Community Health stats. In mid-July, the calmingly low numbers spiked, prompting an audible gasp from us.

Hospice went in a week before my mother died. However, with the virus spreading like wildfire, they could not go back in until July 20, at which time the hospice nurse was pronouncing my mother dead.

My beautiful, sweet (and salty) mother has since been joined in death by 27 of her fellow residents. And still the virus exacts its relentless toll.

One of my regrets is that she never got to return to the CNC. The pandemic caused us to cancel our last appointment. She might have proudly told Stephanie that her title as family memoirist remained uncontested, for she had just helped my sister recall facts about her childhood best friend.

At the CNC, my mother was not a number, despite sometimes being unpredictable. In the course of a visit, she could start out compliant, then go sullen, and not lose any ground with Stephanie. That kind of grace one usually receives only through family members and close friends.

Had my mother been tested again, her rendering of a clock might have needed some work. But her humanity was never in question.