A Propensity to Act

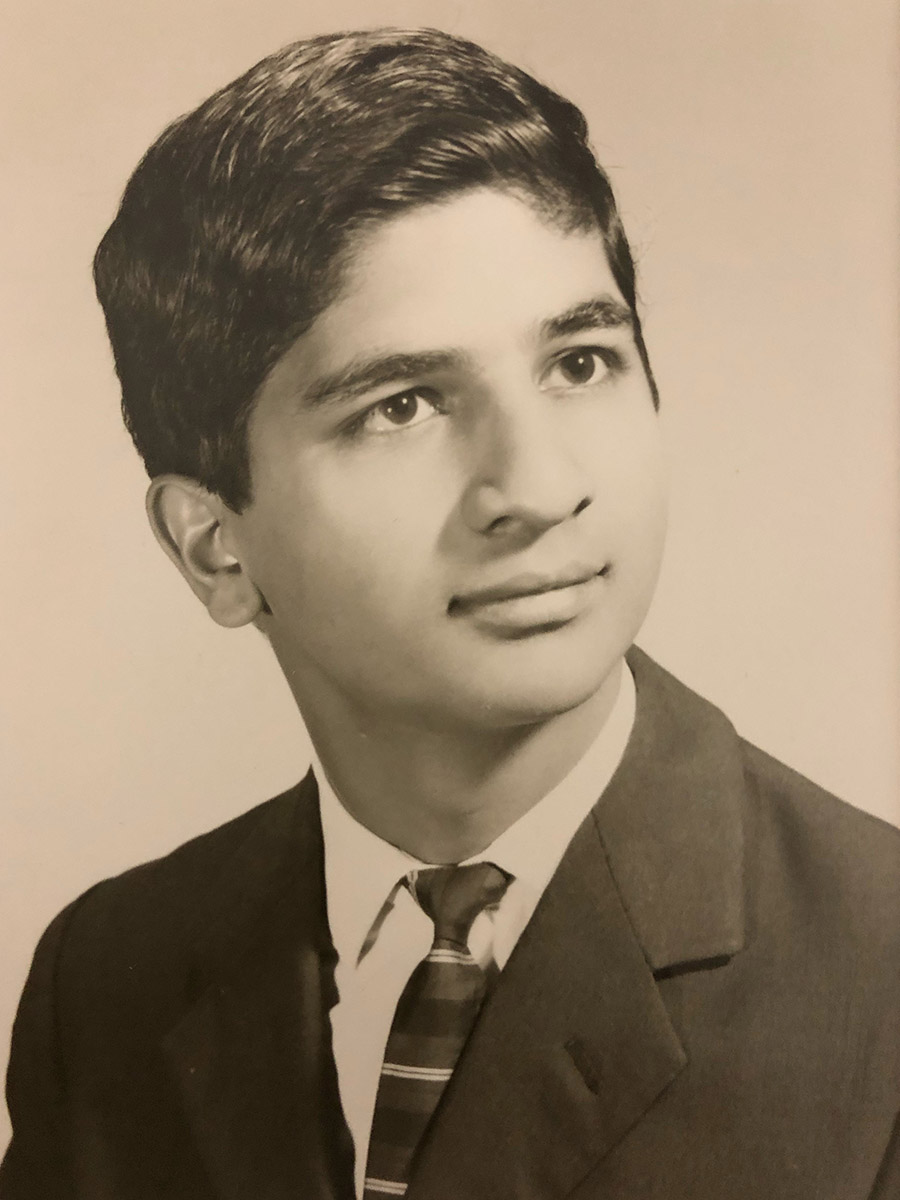

Vikas Sukhatme, Woodruff Professor of Medicine, dean of the Emory School of Medicine, and chief academic officer of Emory Healthcare, came to Emory in late 2017 from Harvard, where he was chief academic officer at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and the Victor J. Aresty Professor of Medicine.

Video Profile

VS >> People are really excited about working with each other. That's not true at every institution. There is tremendous support from the community. That includes the public overall, but also foundations that have been great supporters of Emory in the past and continue to be. And there is an incredibly diverse and talented group of individuals here.

You've described yourself as a "techie at heart, with a quantitative sense of the world." How does that inform your deanship?

VS >> I like numbers, I've always been interested in math and so on. I tend to be data-driven—I like to see evidence, to make decisions based on data and have outcomes we can measure.

Moving as an infant with his family from India to Italy, Sukhatme attended Notre Dame International School in Rome. At 16, he left for college at MIT, where he received a bachelor’s and a doctorate in physics. He went on to receive a medical degree from Harvard.

You've said the deanship of a medical school is a "multidimensional job." What in your life and career has prepared you for your current position?

VS >> I have had the privilege of meeting people from all over the world and gaining diverse perspectives. I'm from India originally, but had the opportunity to grow up in Rome, Italy. From there I moved to the US, from the East Coast to the West Coast to the Midwest, and now, here to the South. What I really enjoy is learning from everybody, and the diverse background that I've had the good fortune of being a part of certainly feeds into that.

We have three missions in the School of Medicine—discovery, teaching, and clinical care—and I've had some experience in each of these. All three have to work together to the benefit of each. That's the exciting part of this job. We must seek every opportunity to connect these dimensions. Every patient encounter is an opportunity to help, share (teach), and discover—with the first always trumping the other two (to paraphrase one of my mentors, Dr. Mitchell Rabkin).

In addition to being dean, you are also chief academic officer of Emory Healthcare. Can you speak to the relationship between Emory School of Medicine and Emory Healthcare?

VS >> We have a very large system—even within Emory Healthcare, there are multiple hospitals and clinics, and that has its own challenges. The physicians who work at Emory Healthcare are largely faculty in the School of Medicine. Faculty also work at the Atlanta VA Medical Center, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, and Grady Hospital. Emory Healthcare provides the School of Medicine with significant financial support for the academic mission, meaning both research and education. In turn, the clinicians Emory Healthcare can attract are of a higher caliber.

How has your own research evolved over time?

VS >> I started out as a basic scientist, asking questions about biology and gene regulation in particular. I am now more of a translational researcher—I look for the applications of what I might discover. I enjoy finding connections between clinical problems and scientific advances within, and especially across, areas.

How important is innovation at an academic medical center like Emory and what are its primary drivers?

VS >> Innovation is a key part of what I and many others in the School of Medicine would like to see as a hallmark of the school. I'm making no bones about it. What is most important is that people connect with each other, that they see that by working together, we can solve the big problems that are out there. That's a necessity these days. No one person or one group knows it all. Furthermore, some of the best ideas come from people who've never worked in the field.

“Our dedication is ultimately to the thousands of patients [our faculty clinicians] serve each year, the immeasurable human impact of our game-changing discoveries, and the clinical excellence and compassion we’ve instilled in the students, residents, and fellows who have learned and trained in our School of Medicine.” --Vikas Sukhatme

You've mentioned some new initiatives the School of Medicine will be involved in to foster these connections across the university and with industry partners.

VS >> We have the Emory Healthcare Innovation Hub, supported by the Woodruff Health Sciences Center, with faculty and staff largely from the School of Medicine. The Hub is devoted to digital health, and opportunities for working with companies in that area. It is building an ecosystem of diverse companies in the health care space that come together, using Emory as the place where they can interact.

There’s also the Biomedical Catalyst program, which started last year and is jointly funded by the School of Medicine and the Woodruff Health Sciences Center. We’re looking for novel ways of interacting with industry as they develop new devices and products, right from the get-go. The Catalyst program encourages Emory medical faculty to be entrepreneurial, providing them guidance along their journey, and is working closely with the university to establish a venture fund to seed novel Emory technologies. It is also interacting with the Biolocity program in the Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering.

A third program is an interface with the university at large, setting up a Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship. It’s being funded primarily by the provost’s office, Goizueta Business School, the School of Medicine, and Emory College. This will be largely directed toward learners—students and trainees.

We’re also working closely with Emory’s Office of Technology Transfer (OTT), looking at how we can be more efficient in getting our ideas out there and bringing entrepreneurs into Emory to help us decide what is worth patenting, for example. At the end of the day, most drugs and devices are developed by industry, so we do need to have an eye on how to best commercialize innovations. OTT provides valuable guidance to faculty seeking to commercialize their inventions.

In fact, you and your wife, epidemiologist Vidula Sukhatme, started a center to encourage innovation. What is its purpose?

VS >> Yes, we have recently established the Morningside Center for Innovative and Affordable Medicine (see sidebar) to address ideas that show promise but lack financial incentive. This center grew out of a nonprofit called GlobalCures that Vidula, an epidemiologist with expertise in health care information systems, and I started a few years ago. We recognized that there are scientifically promising medical ideas that are not being developed because of a lack of financial incentive.

What are the I3 (or I-cubed) awards?

VS >> We’ve set up a number of awards to promote innovation called the I3 awards, which stands for imagine, innovate, and impact. Some of the awards we call the I3 Wow awards. I’m asking our faculty to showcase their best ideas. The I3 Nexus awards are meant to bring people together—ideally, folks who have not worked together before, around a problem that they think they can solve by collaborating. The I3 Venture awards are for ideas that are likely to be successful commercially. We have also I3 awards on the education side.

What has been put into place toward your goal of increasing faculty engagement and making communications a two-way street?

VS >> It is difficult to communicate to a group of 3,000-some faculty, 2,000-plus staff, and 1,000-plus students and trainees, but we need to find multiple avenues to do so. One thing we’re starting is “connectivity chats”—periodic updates from me and other leaders to inform faculty, staff, and learners on the state of the school.

You've said that—in addition to transparency, efficiency, meritocracy, and inclusivity in medical training and practice—there needs to be a "little quirkiness, as well as humor and humility." Can you expound?

VS >> It’s absolutely essential given the seriousness of our work, especially work that directly impacts patients, that we have these qualities in place—just to keep our own sanity, frankly. A little quirkiness helps you think outside the box. Humor allows us not to take ourselves as seriously as we sometimes are apt to do. Humility, we learn very quickly as doctors. If somebody complains to me, I’ll say, let’s take a walk and go over to the wards, and we quickly realize how limited our medical knowledge really is and how ineffective many of our treatments are. Humility also allows you to connect with people because if you’re humble, you will be curious and receptive to learning. And curiosity is critical if you are going to find new solutions.

As leader of an academic medical center that is part of a larger university, how do you elevate the mission beyond rankings?

VS >> Rankings are a surrogate for impact—typically those who rank higher are able to do more things that lead to important discoveries. Our true north is to ask, what impact do our discoveries have? How do they enable better care of those who are suffering from disease? How do we prevent disease? And how well do we serve vulnerable populations?